The services save lives, Health Minister Josie Osborne says. Doctors now running unapproved sites agree.

by Michelle Gamage from The Tyee – Read the source article

B.C. is setting things in motion to build more overdose prevention sites at hospitals, adding to the nine sites that are already open at hospitals like Surrey Memorial and St. Paul’s, according to the Health Ministry.

Overdose prevention sites allow patients to legally use unregulated drugs while supervised by health-care professionals who can step in if there’s a medical emergency such as an overdose. These sites help build trust and relationships, which can be used to connect people with other services, like housing and treatment, the ministry said last Thursday.

The announcement says the province has “given direction” to the health authorities on the “consultation and approval requirements for creating new overdose prevention services at hospital sites.”

A group of doctors who have been advocating for Island Health to open overdose prevention sites in hospitals say they’re cautiously optimistic.

It’s good to see the ministry “basically repeat everything we’ve been saying,” said Dr. Ryan Herriot, a family doctor and addiction medicine specialist in Victoria, and co-founder of Doctors for Safer Drug Policy, an independent group of physicians from across Vancouver Island who work with people who use substances, advocating for compassionate, inclusive and evidence-based care for all.

The Tyee is supported by readers like you – Join us and grow independent media in Canada

The ministry said that when a hospital has an overdose prevention site there is a significant drop in overdoses and a decrease in the number of patients and staff who are exposed to drugs second-hand.

Drug use is not allowed in hospitals outside of overdose prevention sites. Unfortunately this rule hasn’t prevented people from using in their rooms or hospital bathrooms and dying from overdose, or staff from being exposed to drug use.

Which is why opening overdose prevention sites at hospitals seems like a win-win.

“The impact of having on-site overdose prevention services at St. Paul’s Hospital has been profound,” said Dr. Andrea Ryan, program director for the Interdisciplinary Substance Use Program with Providence Health Care, in the press release. “The positive impacts cannot be overstated.”

Since 2019, 58 overdose prevention sites across B.C. have saved 12,400 lives, the ministry said. The First Nations Health Authority says at least 1,024 First Nations lives were saved by overdose prevention sites between 2018 and 2022.

Vancouver Island hospitals have needed overdose prevention sites for years, Herriot said.

Doctors for Safer Drug Policy has been opening unsanctioned overdose prevention sites since November 2024 in Victoria, Nanaimo, Courtenay and Campbell River to meet this need, he said.

Doctors and volunteers have donated their time and money for this harm reduction service after they saw a “stark” increase in unwitnessed overdoses in and around hospitals, he said.

The sites first opened on hospital grounds, only to be chased off by security and confronted by police.

These sites eventually found their groove and will continue to pop up until the government steps up and takes over the role, Herriot said.

Herriot’s one caveat? He says the wording in Thursday’s announcement could let the government open a broad suite of overdose prevention sites soon — or let it sit on its hands and continue stalling.

The government isn’t treating the unregulated toxic drug crisis as the emergency that it is, he said.

In 2023 Island Health started planning ways to open overdose prevention sites at Nanaimo, Victoria and Campbell River hospitals, but then paused this work in April 2024, according to reporting by Filter magazine.

In an email to The Tyee the Health Ministry said these projects were paused to give the province time to write minimum service standards for overdose prevention sites, which it published as part of Thursday’s update.

These standards are “reasonable,” Herriot said. But most overdose prevention sites already meet these standards, he added, so it’s not clear why the province couldn’t build out new sites and write standards at the same time.

The synthetic opioid fentanyl started being added to B.C.’s unregulated drug supply in 2014. This highly potent drug created an exponential increase in unregulated drug deaths, pushing the government to declare a public health emergency in 2016.

As part of that, then-health minister Terry Lake ordered health authorities to open overdose prevention sites “as and when necessary” to reduce overdose fatalities. It’s this order that lets the Health Ministry open more overdose prevention sites in hospitals.

Tragically, unregulated drug deaths have continued to rise and are considered the leading cause of death in B.C. for people aged 10 to 59. As of March 2025, the BC Coroners Service says, 17,655 British Columbians have been killed by unregulated drugs since 2014.

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry estimates around 225,000 British Columbians use unregulated drugs and around 150,000 have a substance use disorder.

This is creating problems when someone who regularly uses drugs needs health care, Herriot said.

Everyone, regardless of if they do or do not use unregulated substances, deserves health care, he said. But by banning all drugs and drug use from hospitals, people who use drugs are being pushed away from accessing care or pushed to hide their use, which can increase their risk of fatal overdose.

‘This Is a Life or Death Facility and It Needs to Operate’

In an email to The Tyee, the Health Ministry said it was protecting patients and health-care workers from being exposed to drugs in hospitals by “working within a zero-tolerance policy for drug use in hospitals.”

Patients who use drugs and who are admitted to major Vancouver Island hospitals are connected with addiction medicine and substance use teams who work with patients to manage withdrawal, “with the goal of supporting patient comfort and reducing the need to use substances while admitted to hospital,” the Health Ministry said.

Herriot said many of the members of Doctors for Safer Drug Policy work on these teams and that while this care plan can “be very effective” for some, it leaves others out in the cold.

“Inpatient care teams are absolutely critical and insufficient,” he said.

That’s because street drugs can be so potent and have people dependent on such a strong dose that existing pharmaceuticals aren’t able to fully prevent a person from going into withdrawal, which pushes them to continue to self-medicate while in hospital, Herriot said.

Stimulant addiction can also be tricky because there’s not a lot of evidence around how to effectively prescribe stimulants in a way that replaces someone’s regular street supply, he said.

And that’s just treating the physical part of addiction.

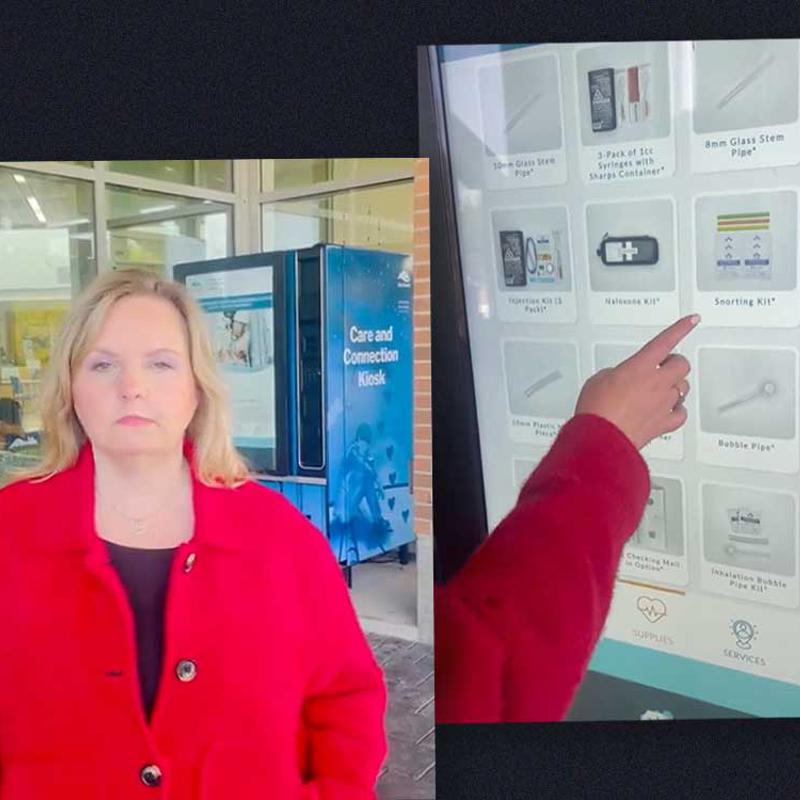

Following Backlash, BC Removes Harm Reduction Vending Machines

Drug use is complex and unique, Herriot said, adding that a common theme is trauma, often stemming from “horrifically traumatic life histories starting in early childhood.”

So treating someone’s physical dependence doesn’t necessarily get at the reason someone was turning to drugs to cope in the first place, he said.

Some patients might not be in a place where they are ready to consider lasting sobriety, he said.

In November a man who used drugs at the Doctors for Safer Drug Policy’s overdose prevention site died later that day when he used again, this time alone in a hospital bathroom because the overdose prevention site was closed for the night.

Saying drugs are banned from hospitals is a “complete denial of reality,” Herriot said. The policy suggests that patients whose complex needs can’t be adequately addressed by the addiction medicine teams will be excluded from, or don’t have a right to, health care.

“If the war on drugs worked it would be over by now,” he added. ![]()

Read more: Health

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.