- Olivier Laurin from Black Press Media delves how the opium poppy sprouted into today’s deadly opioid crisis

This article discusses the opioid crisis and its evolution through time. If you or someone you know is struggling with substance use, support is available. Call BC Addiction Services at 1-800-663-1441, or the Opioid Treatment Access Line at 1-833-804-8111.

– – –

Since the dawn of mankind, humans have sought countless ways to manage and alleviate their pain, whether psychological or physical.

Through the ages, from ancient remedies to modern therapies, one small, unassuming plant has shaped the course of history like no other.

Around 3400 BC, the Sumerians, the world’s oldest known civilization, first cultivated the opium poppy in lower Mesopotamia, calling it Hul Gil, or the ‘joy plant.’

Harvested for its milk-like sap, the poppy plant produces opium, a potent substance that was hailed as a miracle cure used to treat pain and a range of ailments.

As people learned about opium’s virtues, demand for it increased and its use spread throughout the Levant and beyond. The ancient Greeks used it, as did the Chinese and many other cultures worldwide.

It was prescribed on clay tablets, referenced in the Bible, and consumed by artists, philosophers, and society’s highest ranks.

In its name, trade routes were built, empires rose, wars were fought and blood was spilled.

As humanity’s incessant urge to numb pain grew, opium became the root of a crisis few of its early users could have foreseen.

What began as a simple powder evolved into far more potent narcotics, millennia later, that are now crippling communities across the western world, claiming tens of thousands of lives each year.

From opium to morphine, to heroin and fentanyl, this article traces the history of how a narcotic with humble origins became a scourge on B.C.’s streets.

Opium’s arrival in Canada and the advent of opioids

While thousands of Canadians have died in recent decades from the toxic drug crisis, fentanyl isn’t the first substance that has stirred controversy in the province.

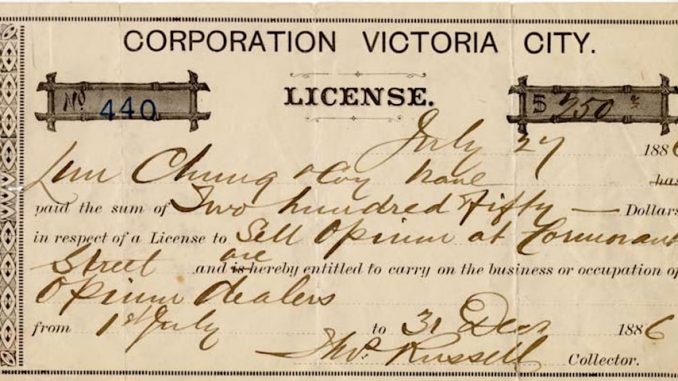

Opium was first brought to Canada by Chinese migrant workers who came to build the nation’s railway system in the late 19th century. Legal at the time, opium was ingested or smoked for medicinal, cultural and recreational purposes.

Often consumed in opium dens, the narcotic gained a foothold in Vancouver, Victoria, and New Westminster.

However, in 1911, the Parliament passed the Opium and Drug Act, championed by McKenzie King, which added opium – among other drugs – to the list of prohibited substances. Scholars argued that the criminalization of the drug was largely rooted in racism, overtly targeting individuals of Chinese descent and other ethnic backgrounds.

A century before this prohibitive legislation, German pharmacist Freidrich Serturner was the first one to chemically tame and magnify opium’s power.

In a series of experiments performed in his spare time, he managed to isolate an alkaloid compound, naturally occurring in the poppy, and discovered morphine in 1806.

Serturner found that the substance affected the central nervous system and brain by blocking pain signals to the rest of the body. At the same time, when consumed, the drug triggered the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward, leading to feelings of well-being. This sudden surge of dopamine is said to partly reinforce substance use, contributing to the development of an addiction.

With 10 times the power of processed opium, Serturner named the substance after the Greek god of dreams, Morpheus, for its sleep-inducing symptoms.

In creating this narcotic, the German pharmacist gave birth to an entirely new group of drugs. Known as opiates, these chemical compounds, which include morphine, are extracted or refined from natural plant sources.

At the tail end of the 19th century, English chemist Charles Romley Alder Wright first synthesized diacetylmorphine, a substance four times more potent than morphine. Years later, the pharmaceutical giant Bayer introduced it to the market under the name heroin.

Similarly to Serturner, Wright contributed to the development of what are now known as opioids, a class of drugs that are synthesized to mimic the effects of natural substances found in the opium poppy.

While opium eventually faded from use in Canada, heroin took its place.

Until the early 1950s, the opioid was prescribed for therapeutic purposes, while illegal heroin began to circulate in the streets of the country’s major cities.

The narcotic first drew widespread attention in B.C. in the late 1990s, when a cheap yet potent strain known as China White entered the illicit drug supply, according to Katy Booth, project coordinator for the University of Victoria’s Substance Drug Checking.

Following an “inordinately high number of deaths” associated with the use of heroin, B.C.’s chief coroner at the time published a report on illicit narcotic overdose death in September 1994. The document stated that between 1988 and 1993, the number of drug-related deaths in the province rose annually from 39 to 331.

A sudden change in the illicit drug supply may have contributed to these casualties, Booth explained.

“Historically, heroin is not causing, generally speaking, a whole lot of overdoses. But when you get a supply that is different, tolerance isn’t there and there are higher risks of overdose.”

What makes opioid overdoses so lethal is how the narcotic depresses the body’s respiratory function, depriving the brain and body of oxygen. When a person takes a higher dose than their body can handle, their breathing can slow to a life-threatening level. Without prompt intervention to reverse its effects, this lack of oxygen can cause unconsciousness, organ failure, and death.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, crack cocaine – a stimulant – became the go-to party drug in B.C. Cheap and relatively easy to use, it could be smoked rather than injected and quickly overtook heroin as the illicit drug of choice in Vancouver’s underground scene.

Like its predecessor, heroin eventually faded from use. But, nearly a decade later, another opioid re-emerged. This time, it was not covertly dealt on the streets but openly prescribed in doctors’ offices nationwide.

Manufactured addiction

With the turn of the new millennium, changes in medicine led to pain being recognized as the “fifth vital sign,” placing it alongside body temperature, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and heart rate.

This paradigm shift meant that pain became a central focus of a doctor’s visit.

In the hope of easing their patients’ pain, the medical establishment, slowly but steadily, started prescribing a pea-sized pill of oxycodone mostly known under its brand name as OxyContin.

“There was a lot of resistance to prescribing opioids for a long time because doctors didn’t want folks to form physical dependencies,” said Booth. “But when there’s this new drug that has come around and ‘doesn’t have the same risks’… it seemed like a great solution.”

Developed by American pharmaceutical Purdue Pharma, OxyContin was released in 1996. Backed by aggressive marketing across North America, Purdue promoted the drug as a 12-hour painkiller, lasting more than twice as long as market alternatives.

This seemingly great resume made it the drug of choice to alleviate a wide range of pains, Booth explained.

“OxyContin was the main (prescribed drug) because they were considered by many as an alternative to habit-forming or physical dependency… and therefore safer to prescribe, but it wasn’t. ”

In 2007, Purdue pleaded guilty to criminal charges for misleading the public, falsely claiming that OxyContin was less addictive and less prone to abuse – when in fact, the opposite was true.

Since the early ’80s, the volume of opioids sold to Canadian hospitals and pharmacies has increased by more than 3,000 per cent. In 2016 alone, over 20 million prescriptions for opioids were distributed to patients, making Canada the second-largest consumer of prescription painkillers in the world, after the U.S. As many as one in five Canadians used a medical-grade opioid during peak years, between 2008 and 2010.

As the harms of widespread narcotic use became clear, federal and provincial governments, along with the medical establishment, launched initiatives to curb both the medical supply and its consequences. These efforts included increasing prescription monitoring and enforcing stricter prescribing rules, among other things.

Following this crackdown, OxyContin was delisted from Canadian drug formularies in 2012 and replaced with a reformulated tamper-resistant form of oxycodone, preventing it from being crushed to be snorted, injected or used in any other alternative ways than orally.

While well-intended, these actions overlooked the impact on the growing number of high-risk opioid users left without prescriptions to manage their dependence.

As the country observed a sharp rise in opioid addiction, thousands who had previously relied on medically prescribed painkillers turned to a flourishing illicit market, where a supply of increasingly potent and cheap narcotics emerged to fill a growing gap.

Although the country’s medical establishment played a significant role in fuelling this growing addiction epidemic, Booth believed that practitioners were not acting with ill intent.

“Doctors would often… want to help a person avoid a life of pain, so I think their intentions were really good. But we started to see a lot more prescribing of opioids for chronic conditions as opposed to it being more of an end-of-life drug or for acute post-surgical pains.”

Today, the medical consensus is that opioids should be a last resort for managing chronic pain.

Yet, the damage was done and the emergence of a new unforeseen and deadlier trend quietly crept in.

“We knew Oxys were being reformulated and we knew heroin was hard to get, but it was difficult to know what would happen (next),” said Booth. “I don’t think many of us thought it would be fentanyl.”

Number one killer

First synthesized in Belgium in 1959, fentanyl was first used clinically as an intravenous anesthetic. It has since become one of the most important synthetic opioid analgesics in medicine, most often used intravenously for pain management during surgery.

It is approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin.

Although difficult to pinpoint exactly when fentanyl first appeared in B.C.’s illicit drug supply, the first reports emerged in 2011.

According to Booth, there are a few reasons that made it the perfect breeding ground for why fentanyl became the opioid of choice on the black market.

Exponentially stronger than heroin, fentanyl is less risky to transport and move around since only a fraction of the amount is needed to achieve the same effect as lighter opioids, said Booth.

More importantly, as the government began cracking down on medically prescribed painkillers without providing proper support or treatment to help users quit, many turned to a black market that was ready to welcome them.

“Just because you make something illegal doesn’t mean it’s gonna stop being used or desired,” said Booth. “What about the people that are already misusing? Are we giving them access to methadone, opioid replacement therapies or alternatives? It was just never a part of the plan, so folks, being the resourceful people that they are, found alternative markets to satisfy their needs.”

This, among other factors, paved the way for what Booth described as a full-fledged opioid crisis.

“Around 2012, we knew that overdoses were increasing but we weren’t quite where we are now. It was the beginning. We could see that things were changing.”

Offering drug-testing services to Greater Victoria residents and beyond, Booth and her team have been at the forefront of shifting trends in the region over the past years, having first heard of fentanyl through anecdotal accounts from clients.

“They (started) telling us… that when they were using their heroin, their face started to tingle, so they knew that there was something that was slightly changing within the supply. That happened to be fentanyl that had started to creep in.”

In April 2016, B.C. declared a public health emergency after a steep and unprecedented spike in overdose deaths. That year, 995 people lost their lives.

By 2016, fentanyl was being found in 42 per cent of toxicology tests following an overdose. In 2023, fentanyl or a fentanyl analog was present in 85 per cent of those tests.

“At the beginning of 2019, the heroin contained fentanyl, whereas in 2020 it switched, where fentanyl rarely contains heroin,” said Booth.

Worrying trends

While there are inherent risks with consuming fentanyl and other opioids, Booth emphasized that the primary cause of death is attributed to the growing toxicity and unpredictability of the street-level supply.

Last year, she noted that the vast majority of samples tested contained fentanyl analogs, which are illicit, and often deadlier, alterations of medically prescribed fentanyl.

“If we were to simply have some semblance of stability within fentanyl, folks would adapt and they would figure out what their tolerances are,” she said. “But when you have an illicit market that is highly criminalized, one sample might be totally fine, but then the next sample can be three times stronger.”

Booth argued that these constant shifts in the makeup of street drugs are largely tied to a nationwide “war on drugs” over fentanyl, which in recent years has become a big-ticket item at the local, provincial, and federal levels.

With enforcement intensifying, the black market looked for alternative ways to supply its clientele. In response, traffickers began producing a wide array of unregulated substances, creating ever-stronger and deadlier drugs, while law enforcement was left reacting after the fact rather than preventing their spread.

In parallel, benzodiazepines, a group of depressant drugs prescribed to treat conditions such as anxiety disorders, insomnia, and seizures, entered the supply chain.

When laced with opioids, benzodiazepines are known “to give legs” to fentanyl, making its effects last longer, while also making it cheaper for users.

Rather than using it for recreational purposes, Booth said this mix, commonly known as benzo-down, serves a basic “survival” function, helping users avoid withdrawal symptoms, which can be fatal.

However, this combination can be particularly lethal, since naloxone, which can temporarily reverse opioid overdoses, doesn’t work in the presence of benzodiazepines, explained Booth. As a result, people consuming laced fentanyl unknowingly and without prior tolerance face a higher risk of death.

Armed with cutting-edge technology, UVic’s Substance Drug Checking’s mass spectrometer – which can identify substances at the molecular level – can detect drugs present at concentrations below five per cent. This allows staff to spot trace substances that can be lethal at concentrations as low as two per cent.

Having tested more than 9,000 drug samples across all their Vancouver Island locations last year, Booth and her team reported that the ever-changing nature of the fentanyl supply, containing increasingly potent synthetic compounds, at lower concentrations, makes it harder to detect, monitor and quantify deadly emerging trends.

And the risk, Booth said, is far higher in communities without such technology, where users can’t detect what’s in their local street supply, including potentially deadly fluctuations.

“We’re in quite a privileged position to be able to identify trace components, but you can’t do that in the majority of the province,” said Booth. “I’m worried that we’re starting to see more things like xylazine and nitazines. They probably exist in other places, but they’re not necessarily seeing them because of limitations.

“As (the supply) is constantly shifting and moving, we need to make sure that technology and innovations are also able to keep up so that we’re able to provide the best possible services and information to folks.”

According to latest numbers, 49,105 apparent opioid toxicity deaths were reported between January 2016 and June 2024 in the country – more than 17,000 of which are from B.C., accounting for a third of the country’s deaths.

The number of lives lost from the toxic drug crisis was so significant that in 2021, it led to a decrease in the average lifespan of B.C.’s First Nations.

Current estimations from the Public Health Agency of Canada suggest that overdose deaths may remain high or decrease through the summer 2025, but not to levels seen before 2020.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.