A local doctor says the province’s new safer supply rules are more about politics than public health.

By Mick Sweetman at the Discourse – Read the source article here

Lenae Silva makes a trip to the pharmacy every day where she gets a slow-release fentanyl patch that covers half her back and a dose of quick-release fentanyl tablets, which she takes half of at the pharmacy and is allowed to take half home for a second dose later in the day.

She started smoking meth at the age of 11 and began using opioids when she was 16. She said she was “heavily addicted” by age 18.

“I ended up having not much space of sobriety through the whole 20 years,” she told The Discourse.

Silva said she “wouldn’t be alive right now” without access to the province’s prescribed alternatives program — also known as safer supply — that seeks to keep people off toxic and deadly street drugs.

Your Nanaimo newsletter

When you subscribe, you’ll get Nanaimo This Week straight to your inbox every Thursday — giving you the first peek at our latest investigations, local news updates, upcoming events and ways to get involved in our community.

However, doctors and harm reduction workers in Nanaimo say changes to the province’s safer supply program means it is less accessible for people who need it most.

Read more

Q&A: Nanaimo artist Lenae Silva on substance use, support and ‘bright endings’

The safer supply program was launched in July 2021 by the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, the MInistry of Health and the Office of the Provincial Health Officer.

This was an outgrowth of guidelines that were developed for health professionals during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic who were treating patients who were at risk from COVID-19, withdrawal and overdoses. It has since supported thousands of people in accessing safer prescribed alternatives to toxic street drugs that they could take home.

In February, a policy change by the B.C. Ministry of Health ended the practice of take-home prescriptions, as part of this program, for new patients.

Some doctors say this change puts the safety and stabilization of people who use drugs at risk and increases the chances that they will return to using toxic street drugs and overdosing.

The interim guidelines require new patients to take a “witnessed” dose of the drug at a pharmacy, and patients who were previously prescribed safer supply drugs would be transitioned to a witnessed dose model.

At the time of the policy change, people who were on the prescribed alternatives program were worried about how the change would affect their lives and if they would be able to manage their medication schedule as well as everything else in their daily life. They worried this change could result in relapsing into using unregulated street drugs.

Dr. Jessica Wilder, a Nanaimo-based family and addictions doctor who works with people who use substances said the change impacts people’s abilities to work, spend time with family, care for children or “any of the freedoms that we all take for granted when we don’t have to be returning to a pharmacy every four hours.”

Silva said she was just becoming stabilized and was ready to start looking for work when “this bomb drops on us.” She said that if she had to take all of her medications at one time, it would impact her ability to function and work.

“I’m going to be sitting half-awake, half-asleep [like] you see with opiate users. It’s just too much,” Silva said.

For users like her that live close to services, it’s possible to go multiple times a day for their medications. But her partner has long-term injuries which makes it difficult for him to go to the pharmacy once, let alone multiple times a day.

She described the push towards a witnessed consumption model as telling a person who wakes up in the morning thirsty that they have to drink all of the water for the rest of the day at one time.

“By the next day, you are so thirsty that you just don’t feel good,” she said.

Data shows fewer people accessed safer supply after change was made

Since the policy change was announced, data from the BC Centre for Disease Control shows that the number of people who have drugs dispensed as part of the prescribed alternatives program fell sharply from 3,869 people in January to 2,959 in May, but since then it climbed for two months to 3,282 people in July. Most of the change was driven by clients in the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority.

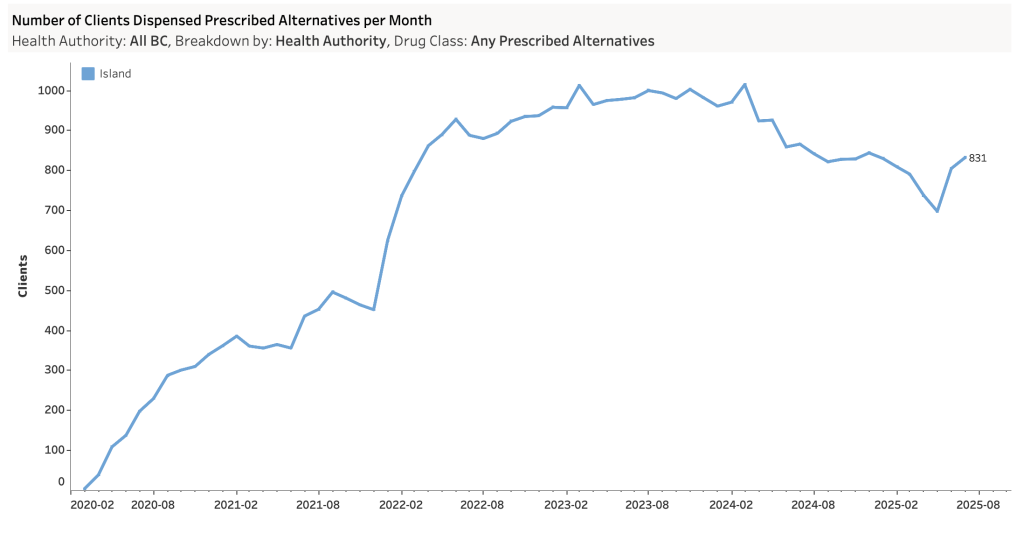

In the Island Health Authority, the number of patients fell from 829 people on the program in January to a low of 697 in May before rebounding to 831 in July.

Part of the reason for that is an increase of 46 new clients being added in June and 41 in July in the Island Health region, the most since February 2024.

In a 2023 report by the provincial health officer, it was estimated that 115,000 people in B.C. live with a diagnosed Opioid Use Disorder. Only 16.5 per cent of people who accessed harm reduction services and were eligible for safer supply had ever received it.

The report found that the reach of the safer supply program was largely limited to people with opioid use disorder who were already connected to the health-care system. This excludes at-risk people who are more marginalized. It also found that safer supply services also exclude people who are not daily opioid users, which means “the majority of people at risk of drug poisoning are not eligible” for the program.

“The whole point of giving them those drugs is because it’s the street drugs that kill them, not the prescribed drugs,” said Ann Livingston, a volunteer with the Nanaimo Area Network of Drug Users (NANDU).

As of August, an average of five people a day die from unregulated drugs, according to the B.C. Coroners Service, and 1,218 people died in the first eight months of 2025. But the death rate is 31.9 people per 100,000 population, its lowest since 2019. Forty eight people in Nanaimo have died from accidental overdoses this year as of the end of August.

A ‘moral panic’ and political reaction

The changes to the safer supply program happened shortly after a spate of media reports of people who were on the program selling the prescribed drugs on the street as well as an investigation into pharmacies who were giving cash payments to people to fill prescriptions at their store.

“There’s a huge confusion in the public about this, and they keep saying, ‘People are dying because you’re giving out safe supply. Children are using drugs or becoming addicts because of safe supply,’” Livingston said. “But if you look at the actual coroner’s data, it doesn’t show that at all. Anyone can start a little moral panic and get it in the papers.”

A 2023 review of the safer supply program by the B.C. provincial health officer found that data showed there “is no increase in Opioid Use Disorder diagnoses amongst youth, or in any age group,” since the implementation of safer supply in the province.

The BC Coroner’s Service reported in 2023 that there was no evidence prescribed safer supply was contributing to unregulated drug deaths. The 2024 unregulated drug death report does not mention safer supply.

Under the new rules, pharmacies are not allowed to fill take-home prescriptions for new patients on the Prescribed Alternatives program, though some patients who were on the program before the changes have been grandfathered in.

Wilder said the requirement that pharmacists witness patients taking the drugs “makes it really challenging” when she sees patients who would benefit from it.

“It’s just not something that we’re even able to do anymore, because pharmacies are not allowed to dispense it for safer supply,” she said.

There is an exemption for “extraordinary circumstances” in the interim guidelines published by the BC Centre on Substance Use and approved by the Ministry of Health.

That exemption says the prescriber can use their clinical judgement on whether moving to a witnessed consumption model for existing clients would “present a significant risk of destabilization.”

“The reality is in our current toxic drug crisis, anybody who accesses unregulated drugs in any way, shape or form is at risk of death,” Wilder said. “I would say that everybody meets the criteria for extraordinary circumstances.”

Wilder blames the NDP government for the changes.

“I think it’s really important to acknowledge that the BC Center for Substance Use released these interim guidelines as a direct command, essentially, from the government,” she said. “These interim guidelines are not based on evidence, they’re not based on data, or even anecdotal experience from addiction medicine professionals. This was a political move.”

The changes to the program took place weeks after the Conservative Party of B.C. released a leaked presentation by the Ministry of Health stating that “a significant portion” of the opioids being prescribed were not used by the intended recipients and are being “trafficked provincially, nationally and internationally.”

In an email to The Discourse, the Ministry of Health said the “BC Centre for Substance Use consulted with each of the regional health authorities’ addiction medicine leads, the First Nations Health Authority (FHNA), people with lived and living experience and other clinicians with expertise in substance use care.”

It acknowledged that there has been a reduction in the amount of hydromorphone prescribed since the introduction of witnessed consumption as a policy.

“This drop is from efforts to change clinical practice to better meet the needs of patients who are more likely to divert because hydromorphone is not meeting their needs,” the ministry said.

It said the province is monitoring and evaluating changes to the prescribed alternatives program to “reduce harm, protect communities and increase access to treatment and recovery services.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.