From Peterborough Currents by Will Pearson

Participants’ lives are stabilizing and improving thanks to safer supply prescriptions, clinic researchers find.

Participants of a safer supply program in downtown Peterborough have experienced positive changes in their lives — including reduced use of fentanyl and fewer overdoses — since enrolling in the pilot project, according to two new reports released by the clinic that operates the program.

“People have experienced a dramatic reduction in overdoses,” said Kathy Hardill, a nurse practitioner who prescribes safer supply opioids at the 360 Degree Nurse Practitioner-Led Clinic. “People have reduced their fentanyl use quite dramatically.”

Hardill said she’s worked with people experiencing homelessness and using drugs for most of her 35-year career in health care. But watching people progress through the 360 Clinic’s safer supply program “has been one of the most satisfying types of work I’ve done in all my years,” she said.

Funded by Health Canada, the program offers prescriptions to a regulated supply of opioids with a known potency. The idea is to give people who use drugs a safer and medically supervised alternative to the unpredictable and often deadly supply of drugs currently available on the streets of Peterborough.

In addition to the prescriptions, participants gain access to a range of services, including primary health care, mental health counseling, community programs, and social services, according to program manager Carolyn King.

The program accepted its first participants in the spring of 2022 and had 41 participants as of May 2024, according to the clinic. To be eligible, participants need to have an opioid use disorder that has caused life-threatening complications and be using fentanyl on a daily or near-daily basis. They also need to have tried other treatment options such as a traditional methadone program without success. Most participants are precariously housed and experiencing food insecurity and poverty.

Researchers collaborating with the 360 Clinic have been evaluating the program since it started, primarily by interviewing participants and analyzing their medical records. At an event on June 12, the clinic released two reports that present the researchers’ findings.

According to the reports, researchers audited the medical records of 29 participants. At the time of their enrollment, 34 percent had experienced an overdose in the previous six months. Six months into the program, that number had dropped to seven percent.

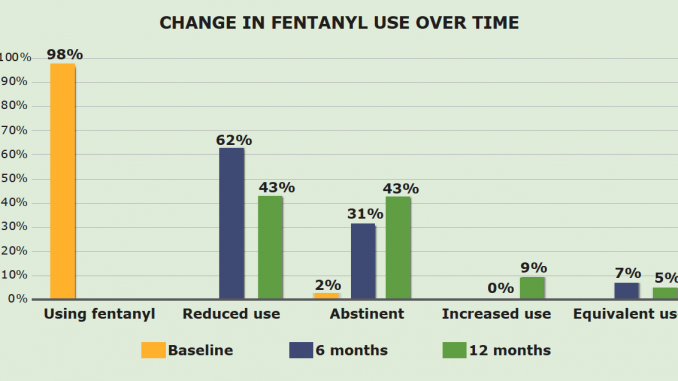

Another finding: Of the 23 participants whose records were audited after 12 months, 43 percent said they had stopped using fentanyl entirely and another 43 percent reported a reduction in their fentanyl use.

Numbers are one thing, but for King, the program’s success can also be seen in the participants themselves. She said many were experiencing despair, hopelessness, and low self esteem when she first met them. Now, they’re holding themselves higher and pursuing new goals in life, such as accessing housing, reconnecting with family, or looking for employment, she said.

The hustle to obtain street-sourced drugs “is a 24-hour job,” King said. “It is almost impossible to attend to anything in life when you are in constant survival mode [and] hunt mode.”

With a safer supply prescription, drug users are free to focus on other life goals instead of constantly seeking drugs, King said. “Our program gives people that ability to start tending to other parts of their life.”

After 12 months in the program, 94 percent of the 18 participants who filled out a survey said their lives felt more stable, according to the reports.

And 71 percent of participants who took the survey said they were engaging less in criminalized activities.

Two interviewees said they had been able to end their involvement in survival sex work, according to the reports.

“It helps because I don’t have to go out and do stuff that I don’t want to do to get drugs,” one participant was quoted as saying in the reports.

Peterborough’s police chief Stuart Betts told Currents that if the programs “are successful in moving people away from criminal activity, then that is positive for them and all members of our community.” But he also stated that there “is no data to suggest safer supply has had an impact one way or the other on criminality in our city.”

Program prescribes hydromorphone, a controlled substance much less potent than fentanyl

The safer supply program offers people access to two complementary drugs to help them manage their addiction. Participants receive a daily dose of a long-acting opioid such as methadone in addition to a daily dose of hydromorphone tablets.

Participants typically take their dose of the long-acting opioid at a pharmacy, but they’re given their dose of hydromorphone to take away with them and administer as needed with guidance from their prescriber, King explained. There are currently 13 local pharmacies who partner with the clinic to dispense the medications, according to the reports.

The long-acting opioid dose is no different from what drug users can access at various clinics throughout the city through traditional opioid agonist treatments (OAT) such as a methadone or suboxone program.

It’s the hydromorphone that sets a safer supply prescription apart from an OAT prescription.

Hydromorphone is a quick-acting opioid also known by its brand name, Dilaudid, and a slang term, “Dillies.” It is a common drug in Canadian healthcare that is often prescribed as a painkiller, including to people recovering from surgery or experiencing pain caused by cancer.

One difference between long-acting opioids and hydromorphone is that long-acting opioids only reduce withdrawal symptoms without providing a high, whereas hydromorphone can provide a high.

According to John Habib, a pharmacist who dispenses safer supply medications at the Burnham Medical Pharmacy, on Burnham Street, the hydromorphone prescriptions are an additional option for people that have tried OAT but not succeeded.

Habib dispensed methadone and suboxone for years before beginning to offer safer supply. And while he saw those medications work for some people, many others relapsed repeatedly and returned to the street supply because they needed something stronger than their OAT prescriptions provided, he said. OAT treatments like methadone and suboxone are “clearly not working” for everyone, he said.

One issue with daily OAT doses is that some people can’t make it to the next dose before they experience withdrawal symptoms, Habib said. That’s where the hydromorphone comes in. “Whenever you feel your dose is wearing off, that’s when you would top up with the Dilaudids. And then that will carry you over until the next time that you’re due [for your daily long-acting dose],” he said.

King said the safer supply program’s retention rate of 84 percent is one thing that sets it apart from OAT programs, which she said have “notoriously low retention rates.”

“As medicine is evolving and adapting we need to be open-minded with the different options,” Habib said. “We need to evolve and figure out what we can do to find success for these patients.”

Habib said he’s noticed a difference in the demeanour of the patients who pick up their prescribed drugs at his pharmacy. “It’s been very positive in terms of patient outcomes,” he said. “We definitely noticed a change in their overall look and behaviour as they get deeper into the program and as they establish their stability.”

In a safer supply program, a Dilaudid prescription is meant to serve as a replacement to street drugs. But in practice, it can’t do that fully, King said, because it doesn’t come close to matching the potency of fentanyl, which is “beyond anything we’ve ever seen in the illicit drug supply.”

That means people who have developed an opioid tolerance by using street drugs “need quite a lot” of Dilaudid for it to have the desired effect, King said. “And even the most Dilaudid that we can provide to somebody is still not going to be quite as much opioid as fentanyl.”

Currently, the program’s guidelines allow prescriptions of up to 30 pills a day, and most participants receive between 20 and 30 pills daily, King said. Doses are determined by a nurse practitioner after a “rigourous assessment” of the patient, King said.

King said the inability to prescribe fentanyl is “a huge limitation of our program, because fentanyl is what is decimating Peterborough, the unregulated fentanyl.”

Some participants reported continued use of street fentanyl during the program, but a total of 86 percent were using less fentanyl or none at all after 12 months in the program, according to the research reports.

Provincial drug plan pays for safer supply drugs, not federal government

The federal government doesn’t directly cover the cost of the drugs themselves. Those are paid for through the Ontario Drug Benefit, which anyone on Ontario Works (OW) or the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) is eligible for.

“It’s the same as any other prescription,” King said.

In Ontario, any physician or nurse practitioner can prescribe Dilaudid as an intervention to treat opioid use disorder, Hardill said. That’s been the case since 2017 when nurse practitioners in the province were given the ability to prescribe controlled substances.

But Hardill said there has been hesitancy among nurse practitioners to prescribe safer supply, partly because the doses needed to match the potency of street drugs go far beyond the guidelines developed for pain management. “There’s a disconnect between what their comfort zone is and what is needed in this public health emergency,” Hardill said.

In addition, “There are many prescribers who don’t understand how toxic the [illicit] drug supply is [and] who hold stigmatized views of people who use drugs,” Hardill said. “So you have a whole bunch of people with the potential to be prescribing [safe supply], who don’t actually have the knowledge or the benefit of understanding why it’s important.”

Critics allege safer supply makes the opioid crisis worse

The 360 Clinic is releasing its reports at a time when safer supply programs are under fire across the country. Critics say the drugs prescribed under the programs are being resold on the street – sometimes to young people who then get hooked on more dangerous drugs like fentanyl. According to these critics, safer supply programs are making the opioid crisis worse.

King called those claims misleading. “They’re not grounded in any kind of data,” she said.

Peterborough-Kawartha MP Michelle Ferreri has made the argument herself, claiming that drug dealers are selling diverted Dilaudid tablets to high school students in a recent House of Commons speech posted to social media.

When Currents asked Ferreri for evidence that this was happening by email, her chief of staff responded by referring to comments made in March by Corp. Jennifer Cooper of the RCMP in British Columbia. Cooper had said organized crime groups were actively redistributing safer supply medications, according to the National Post. However, these comments were quickly backpedaled by a more senior RCMP officer and the B.C. solicitor general, who both stated there was no evidence of widespread diversion of safer supply medications.

One police officer in Ottawa and the deputy chief of the Vancouver Police Department have stated diverted safer supply drugs are being resold on the streets, according to media reports also shared by Ferreri’s chief of staff.

Peterborough police chief Stuart Betts told Currents in a statement that there is “always the potential and concern for diversion of safe supply, but at this point, we lack sufficient data to draw any concrete conclusions. Information at this time is anecdotal only.”

Last year, a doctor in British Columbia who opposes the current safer supply programs wrote in the Globe and Mail that while there is a lack of evidence to support the contention that safer supply is fueling the addictions crisis, in this case “anecdotes must be seen as evidence enough.” He wrote that he’s heard “story after story of how [British Columbia’s] safe-supply program is drawing our young people into the dark world of the opioid epidemic.”

Conservative leader Pierre Pollieve has promised to “put an end” to safer supply programs if elected prime minister. And in May, Ontario premier Doug Ford called on Ottawa to stop approving safer supply sites and conduct a review of existing ones.

King doesn’t deny that some diversion of safer supply medications is happening, and she said her program has policies in place to mitigate the risk. But she disputes the idea that it is a widespread issue that is fueling the opioid crisis and creating new addictions. “We are not causing the opioid epidemic,” she said.

King is sceptical that police could identify the source of any seized Dilaudid pills. “There’s no way to trace the trajectory of [an] individual pill back to somebody that is on safer supply,” she said.

That’s because safer supply programs are not the only potential source of diverted hydromorphone. Peterborough’s medical officer of health, Thomas Piggott, said there are likely thousands of people who have opioid prescriptions for pain in Peterborough, compared to just “a handful of people” who receive opioids through a safer supply program.

“Diversion is a bad thing … and I can appreciate and understand where people are coming from with those concerns,” Piggott said. “But I think that the likelihood that safer supply programs are a primary source of diversion is very, very low,” he said.

The Peterborough Regional Health Centre prescribed 621 doses of Dilaudid to outpatients in April 2024, hospital spokesperson Michelene Ough stated to Currents. The size of a dose varies based on the patient’s needs, Ough stated.

“Diverted Dilaudid has always been a thing,” according to King, who said she herself used Dilaudids long before any safer supply programs started. Dilaudids were King’s “drug of choice” for years, she said, and she “never had a problem finding them” in Peterborough.

“Dilaudids were always available in the street market — always,” she said.

According to a separate peer-reviewed study authored by the 360 Clinic’s research team, some participants said they have shared or sold some of their safer supply medications to friends. Of the 14 people who participated in interviews for the research study, four mentioned this.

But no participants mentioned sharing their prescribed drugs with youth or anyone who didn’t already use opioids, according to the study. Instead, they shared their drugs with friends and loved ones who already used drugs and were going through withdrawal or experiencing pain, the study stated.

King said diversion should be understood as a practice of “mutual aid” among drug users who know their loved ones are vulnerable to overdose or withdrawal as long as they rely on the street supply.

“I’ll take the chance of getting into trouble giving away part of my prescription, you know, rather than see that person die,” one program participant was quoted as saying in one of the 360 Clinic’s reports.

And King argued that reselling prescription drugs “is usually a result of unmet needs.” People sell their drugs because their dose isn’t strong enough, or because they’re living rough and need money for shelter, for example.

As she sees it, the solution to diversion is meeting people’s basic needs. King said staff at the 360 Clinic work with participants “to see where we can support getting those needs met so that their safer supply prescription can be used as intended.”

According to Hardill, the attacks directed at safer supply programs are all about politics. “I think [the] ideologically-based attempt to score political points on the backs of very vulnerable people is disgusting,” she said.

Safer supply programs a reversal of previous decade’s “crackdown” on opioid prescribing

The drug poisoning crisis is accelerating in Peterborough and across Canada. In the Peterborough region, someone now dies from an opioid poisoning every five days, on average, and emergency room visits for drug poisonings are a daily occurrence.

According to Piggott, the crisis isn’t getting worse because significantly more people are using drugs. It’s getting worse because the drugs people are using have become more toxic. https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/lOqyX/1/

How did things get so bad? Piggott said opioids have been used both medically and recreationally for centuries.

But usage patterns began shifting in the 1980s, Piggott said, as pharmaceutical companies marketed their drugs more aggressively and claimed they weren’t addictive. As a result, the medical community “normalized the prescription of opioids,” he said.

Then, in the late 2000s, doctors realized people were, in fact, becoming addicted to prescription opioids.

“The medical community started to crackdown on prescribing,” said Piggott, who remembers being taught to fear opioid prescribing when he was in medical school in the early 2010s.

That crackdown had a disastrous impact on people who had already become dependent on opioids or who needed them to manage pain, according to Piggott. “Many people that were using a stable, safe supply of opioids … were pushed to the street,” he said.

At the same time, the street supply of drugs was becoming increasingly toxic. So, as people were de-prescribed from their relatively safe supply of pharmaceutical opioids, they were pushed to an unregulated supply that was “far more dangerous than it had been in generations past,” Piggott said.

And in the decade since, the street supply of drugs has only gotten more deadly and unpredictable, as fentanyl and carfentanil have become the norm and adulterants like benzodiazepines — sedatives that are immune to the effect of the overdose-reversing drug Naloxone — creep into the illicit supply more and more often.

Nearly all the participants of the 360 Clinic’s safer supply program were using these toxic street drugs when they started the program. And some said the path they followed to the use of street drugs was similar to the one described by Piggott.

During interviews conducted with 16 program participants in January 2024, 13 associated physical and mental pain with their start of opioid use, and 10 noted a history of prescription opioids when describing their path to using street drugs, according to the reports.

With this historical context in mind, the researchers at the 360 Clinic argued in their peer-reviewed article that safer supply initiatives “can be understood as efforts to re-prescribe a safer supply of opioids to those who have suffered the horrific outcomes of deprescribing over the past 13 years.”

360 Clinic’s program funding to expire next year, but two other safer supply clinics now operate in Peterborough without federal funding

The federal government first announced funding for the 360 Clinic’s safer supply pilot in May 2021. At that time, the project was intended to last a little more than two years. Funding has since been increased and was twice extended for an additional year, with the most recent extension coming in March 2024 — just weeks before the program was set to end, King said.

That was stressful, King explained, because program staff had already informed participants the program was ending and started to make transition plans. “There’s lots of harms documented from what happens when you suddenly cut people off from things like safer supply,” King said.

The program’s current funding lasts until March 2025, and Health Canada has been clear there will be no further extensions, King said. To date, funding for the project has totaled $1.6 million, according to Health Canada.

King explained that when the program funding does expire, patients won’t lose access to their prescriptions. The 360 Clinic offers primary care to many people besides safer supply participants, and the plan is for the clinic to absorb safer supply participants into its normal practice. Participants will lose the dedicated “wraparound” services, scheduling flexibility and community programming they gain through the federally funded program, but they won’t lose their prescriptions, King said.

Meanwhile, safer supply is becoming more accessible in Peterborough even without federal support. According to King, two local opioid agonist treatment providers have also begun offering safer supply prescriptions: New Dawn Medical on Burnham Street and Above and Beyond Recovery on Aylmer Street.

New Dawn Medical rents space in the same building as Burnham Medical Pharmacy, but the two businesses are unrelated, according to Habib.

New Dawn Medical offers addiction treatment services at more than 20 locations throughout Ontario, according to its website. According to the clinic’s medical director David D’Souza, New Dawn has about 100 patients in Peterborough who receive safer supply prescriptions through the clinic. Most of New Dawn’s prescribing doctors are based in the GTA and offer patients a combination of virtual and in-person care, he said.

Prescriptions written at New Dawn and Above and Beyond are dispensed at various pharmacies, just like prescriptions from the 360 Clinic are.

That means some of those patients are likely to show up at John Habib’s pharmacy, and he said he’s happy to continue providing access to the medications.

“At the end of the day, these people are here to try to get help,” he said. “They’re here because they have tried in the past and were not successful on their own. So they’re here to improve and get another chance.”

https://peterboroughcurrents.ca/in-depth/360-clinic-safer-supply-evaluation

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.