A logical step forward in harm reduction.

From the International Journal of Drug Policy, Sept 2024 – Click to read the Original Article

Abstract

In 2022, the Drug User Liberation Frontʼs Compassion Club and Fulfillment Centre emerged as a groundbreaking initiative and research endeavor aimed at addressing the alarming rise in overdose deaths within Vancouverʼs Downtown Eastside. As the first of its kind, this pioneering model operated as a non-profit, low-barrier, and non-medicalized approach to regulating the volatility of the content of the illicit drug market in order to prevent overdose deaths. Going beyond traditional overdose prevention methods, the Drug User Liberation Frontʼs Compassion Club and Fulfillment Centre not only provided supervised consumption services, but also supplied rigorously tested cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine at cost to club members. This intrinsic case study offers a unique perspective on the operation of Drug User Liberation Frontʼs Compassion Club and Fulfillment Centre, delving into its inception, development, implementation, and the challenges it faced in its operation. Ultimately, the insights garnered from the Drug User Liberation Frontʼs Compassion Club and Fulfillment Centre hold significant value for others interested in establishing similar programs or exploring de-medicalized approaches regulating substances in order to prevent overdose deaths.

Previous article in issueNext article in issue

Keywords

Compassion club

Drug user liberation front

Overdose prevention

Drug market regulation

Non-medicalized safe supply

Introduction and background

Over the past two decades, a significant surge in worldwide drug overdose deaths has been observed, with North America experiencing a particularly alarming rise. This increase is largely attributed to the widespread presence of the synthetic opioid fentanyl (Penington Institute, 2022), which became an economically viable replacement for heroin after the deprescription of opiate pills (Ciccarone, 2019). Overdose deaths resulting from the toxic drug supply have also been exacerbated by structural factors, particularly the insufficient and unsustainable funding for harm reduction initiatives and limited access to care (Nguemeni Tiako et al., 2022). In 2023, in the United States, using the population midpoint for the year (US Census Bureau, 2024), the crude overdose death rate soared to 32.1 per 100,000 individuals (National Vital Statistic System, 2024), a staggering increase of over 5.4 times compared to its rate in 1999 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). In Canada, the 2023 crude death rate was 20.3 per 100,000 people, which, while lower than several of its international counterparts, was still three times higher than its 2016 rate of 7.8 per 100,000 (Government of Canada, 2023a). The province of British Columbia (BC) has been particularly hard-hit, with the provincial rate spiking to 46.4 per 100,000 individuals in 2023, almost six times higher than its rate of 7.9 per 100,000 individuals in 2014 (BC Coroners Service, 2023). The crisis is now emerging in other geographical areas as well, with Scotland being exemplary as the worst hit in Europe, reaching a per capita overdose death rate of 25.2 deaths per 100,000 people, 4.6 times as many deaths as in 2000, and more than 3.5 times higher than the rest of the United Kingdom (Penington Institute, 2022).

Antedating futural devastation, on April 14, 2016, BC’s Provincial Health Officer declared a public health emergency under the provincial Public Health Act due to increasing concentrations of fentanyl in the illicit drug supply, which was noted as leading to a significant increase in drug-related overdoses (BC Ministry of Health, 2016, p. 2). From that time until June of 2024, the ongoing crisis killed more than 14,500 people in the province of British Columbia alone (BC Coroners Service, 2024). The Downtown Eastside (DTES) of Vancouver, BC, Canada, is at the acute edge of this public health crisis with a 2023 overdose death rate of 556.8 per 100,000 people (BC Coroners Service, 2023, p. 2). This is a rate 12 times higher than BC’s 2023 rate, and 27 times the 2023 Canadian national average. A variety of interventions have been introduced in BC to attempt to reduce the number of drug toxicity deaths, including drug-checking services, overdose prevention and supervised consumption services, virtual overdose prevention, take-home naloxone kits, decriminalization of possession of small amounts of certain drugs, expanded addictions and recovery care, enhanced medication assisted treatment, and access to a prescribed safer supply (BC Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, 2023). Nevertheless, ongoing political tension has resulted pushback against many of these measures, including backlash against safer supply programs (Cole Schisler, 2024) and the recriminalization of drugs in public spaces (Major, 2024). Meanwhile the ongoing public health crisis continues to escalate with no sign of abating.

On November 1st, 2023, a BC Coroner’s Service Death Review Panel of “preventable deaths caused by the unregulated drug supply” (BC Coroners Service Death Review Panel, 2023, p. 3) stated that that “providing people at risk of dying with access to quality controlled, regulated alternatives is required to significantly impact the number of people dying” (BC Coroners Service Death Review Panel, 2023, p. 10). To this end, the report notes that:

Because the current prescriber-based model is unable to address the scale of the public health emergency and the needs of people who are either unable to access that program or whose needs cannot be addressed by that program, a lower barrier, non-prescriber model to support expanded access to regulated drugs has become more urgent (BC Coroners Service Death Review Panel, 2023, p. 10).

The report further outlined a multiplicity of challenges facing the medical system in implementing a safer supply via prescribers including: the inappropriate application of the medical model for those who use illicit substances but do not have substance use disorder; concerns related to cultural appropriateness and cultural safety that exist in the health care system; the limited hours of operation of prescribers and pharmacies; the limited implementation of safer drug prescribing among prescribers, especially outside of urban centres; issues related to diagnostic and monitoring requirements such as urine drug screens and witnessing of drug consumption, the lack of accessibility to primary health care providers (approximately 1 million British Columbians do not have a primary care provider); and the limited scope of available pharmacological options, including both limits of potency as well as route of administration (BC Coroners Service Death Review Panel, 2023, p. 29). These challenges are further echoed by academic literature around the implementation of safer supply programming (Karamouzian et al., 2023).

In August 2022, preempting the BC Coronerʼs Death Review Panel and acknowledging the critical gap in care highlighted by their report, the Drug User Liberation Front (DULF) pioneered the first-ever non-profit, low-barrier, and non-medicalized model to regulate the illicit drug market, responding directly to the escalating overdose crisis in the DTES. Despite facing an untimely conclusion with the arrest of two of DULF’s founders in October 2023, the project yielded positive outcomes. Current literature, as evidenced by Kalicum et al. (2024), attests to the programʼs significant protective effects against overdose.

Ultimately, and despite promising program results, very little remains known about DULF as an organization and the operational structure of its CC&FC. The present intrinsic case study was therefore initiated to document the origin, structure, and activities of DULF’s CC&FC during its operation, and how the projects approach ensured person centered, quality care for its membership.

Sources and analytical considerations

Aligned with DULFʼs foundational principle of “nothing about us without us,” this essay is authored by two of DULFʼs founders. It unfolds with a central aim being an exhaustive exploration of DULFʼs CC&FC through an intrinsic case study approach (Crowe et al., 2011). The information presented herein were gathered using a diverse range of methods and sources, with particular emphasis placed on organizational documents, press reports, and firsthand ethnographic observations conducted through direct involvement in the project.

It is important to note that DULF has maintained constant communication with both law enforcement and the healthcare systems, diligently informing them of its activities. DULF has consistently prioritized transparency by openly sharing information about its endeavors with the press, local police, and the Canadian Government. This commitment to accountability and honesty has, in turn, led to extensive documentation of DULF’s activities by both local and international media.

This paper examines data collected in line with the its objectives, including the description of the origin, structure, and activities of DULF’s CC&FC (reference Fig. 1 for a complete timeline). Members of the research team conducted several reviews of the materials to capture key constructs. Subsequent reviews were used to assign data segments to categories and examine negative evidence. Sections of organizational documents, media files, and field notes were sorted according to the essayʼs objectives and analysed for thematic congruence. Following the merging of all data, DULF members provided feedback on draft summaries of the results.

Origins and program development

Following the publication of the BCCSU’s Heroin Compassion Club White Paper (British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, 2019) and CAPUD’s Safe Supply Concept Document in February 2019 (Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs, 2019), DULF found its origin at Safe Supply 2019, a conference focused on real solutions to mass overdose death, which occurred October 17–19, 2019 (Moakley, 2021). The conference was divided into two distinct sections: one dedicated to addressing the necessity of a medicalized safer supply, and the other centered around exploring non-medical alternatives such as compassion clubs and substance use navigators (Nyx & Kalicum, 2019). The second half of the conference underscored the specific point that collaboration and grassroots initiatives were a crucial necessity to effectively address the challenges posed by the current state of unregulated drug use.

On June 23, 2020, inspired by the success of user-driven direct action such as overdose prevention initiatives pioneered by the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (Kerr et al., 2006), a group of activists, many of whom had participated in the conference, mobilized in Vancouverʼs DTES under the banner of the “Drug User Liberation Front”. The group took concrete steps to push harm reduction forward by distributing over one hundred Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) tested and individually packaged doses of cocaine and raw opium (Fig. 2), with the primary goal to raise awareness and prompt action in response to the escalating lethality of the drug supply in Vancouver (Harmony, 2021).

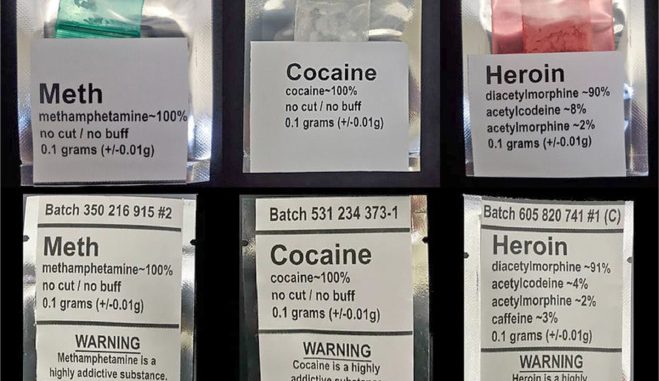

DULFʼs initial action led to the genesis of a model for tested drug distribution and subsequent follow-up with recipients, later named the “Episodic Compassion Club” model. This model’s development was further propelled by a series of events and direct actions. The first, almost a year after the initial giveaway, on April 14, 2021, was fuelled by an intensified sense of urgency considering the worsening overdose crisis. This time, DULF provided clean and tested cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine meticulously packaged into small cardboard boxes (Fig. 3) labelled with contents and accompanied by health warnings (Crack Cloud, 2021).

Subsequent demonstrations followed. On July 14, 2021, outside the Vancouver Police Department, in collaboration with Vancouver city councillor Jean Swanson, DULF distributed ounces of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine to local drug user groups (Pot TV, 2021). Another action unfolded on August 31, 2021, International Overdose Awareness Day, in partnership with Moms Stop the Harm (Nyx, 2021). On this day, DULF orchestrated a province-wide substance giveaway, providing quality tested cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine to drug user groups across every Health Authority in British Columbia, for distribution to their own screened and participating membership.

Concurrent with the action on August 31, 2021, and following a period of ongoing development, DULF took a significant step in legitimizing its actions by submitting a Section 56 Exemption Request from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) to Health Canada to establish a legally sanctioned Evaluative Compassion Club and Fulfillment Centre, ideally using pharmaceutical drugs, or, alternatively, drugs from the illicit market should this option not be available. This comprehensive request included a fifty-six-page report, complete with letters of support, relevant citations, signed affidavits, sworn statements from people who use drugs, and appended additional letters of support (Drug User Liberation Front, 2021a). The exemption request aimed to create a limited stopgap measure, intervening to prevent death in the DTES until Health Canada could formulate more suitable and long-term strategies to address the overdose crisis. Following this request, DULF proceeded to apply for a supplementary Health Canada Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) grant, seeking funding to assess and evaluate the potential activities of the Compassion Club (Drug User Liberation Front, 2021b).

Starting in December of 2021, while awaiting a response from Health Canada and aiming to maintain pressure on provincial and federal governments, DULF initiated a crowd-sourced sustainer donor campaign. This campaign allocated raised funds to consistently provide a tested and labelled supply of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine to drug user groups in Vancouver whenever the BC Coroners Service released data on illicit drug toxicity deaths. This evolving initiative eventually advanced into the DULF’s Dope on Arrival Program, a nearly monthly series of Episodic Compassion Clubs that continued until the arrest of the organization’s founders in October 2023 (Drug User Liberation Front, 2023c).

In March of 2022, DULF’s Health Canada SUAP application was rejected. Then, after 332 days and approximately 2182 preventable overdose deaths in BC following the submission of the Section 56 exemption request (BC Coroners Service, 2023), DULF received a rejection from Health Canada dated July 29, 2022. The rejection of DULFʼs Section 56 request was taken to Judicial Review without delay, a process which continues its course at the time of writing. Nevertheless, despite legal issues and in the face of mounting overdose deaths, the successive rejections prompted DULF to take matters into its own hands.

Provoked by the rejection of DULF’s Section 56 Exemption and SUAP application, DULF took the initiative to operationalize the CC&FC as a dedicated project. DULF contacted all relevant authorities at this time to notify them of the intention to run the requested project, with or without sanctioning. This included the federal and provincial Minister of Health, and the federal and provincial Minister of Mental Health and Addictions, it also included members of the Vancouver Police Department, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, due to DULFʼs presence and presentations at monthly BC Drug Overdose and Alert Partnership.

Program structure

Meaningful community involvement

DULF began its project grounded in the principle of “nothing about us without us,” and actively sought community guidance through regular meetings with the membership of various drug user groups, as well as weekly input from an Indigenous Advisory board consisting entirely of individuals with lived experience of drug use. DULFʼs Indigenous advisory meetings continued to occur weekly throughout the programʼs duration, while community meetings initially maintained a weekly cadence before transitioning to ad hoc as the program stabilized and its organizers faced increased burnout. DULF also implemented a thorough internal program evaluation throughout the existence of its club, and information was used to judge the programʼs effectiveness and improve services throughout the program’s existence. Further, to enhance the rigor of the evaluation, we engaged University affiliated researchers to support this effort.

Governance and funding

Following the submission of requests to Health Canada on October 19, 2021, three board members proceeded to formally incorporate DULF to facilitate management and funding reception. Funding for DULF was provided by the Canadian Mental Health Association via its Community Action Initiative, as well as by Vancouver Coastal Health. In alignment with DULFʼs mandate, its board members actively engage as a working board, shouldering governance duties while also participating directly in daily organizational activities. This integrated approach ensures effective risk management for individuals involved in the organization’s programs, with the board assuming direct responsibility for DULF’s actions. Presently, this responsibility is managed through seamless coordination of strategic oversight and hands-on involvement in fulfilling the organization’s objectives.

Fulfillment centre and compassion club

In essence, the DULF CC&FC model itself is best comprehended as two distinct entities: the Fulfillment Centre, responsible for sourcing, testing, and accurately labelling substances; and the Compassion Club, tasked with screening and enrolling members, distributing substances, and conducting evaluation follow-ups with participants. This dual-institutional approach reflects a comprehensive strategy intended to safely meet the diverse needs of the organization’s program, which was to offer an alternative to the unregulated street supply of illicit drugs.

The core responsibilities of DULFʼs Fulfillment Centre encompassed acquiring, packaging, and labelling substances before transferring them to the compassion club. Despite not being the ideal arrangement, DULF’s Fulfillment Centre was collocated with its Compassion Club. Administrative staff from DULF worked on-site while the Compassion Club was closed, a measure taken to mitigate risks for the program, as well as for program staff and volunteers. Equipped with essential tools such as a time-delayed safe, individual baggies, scales for each substance, a heat sealer, and other specialized equipment for packaging each type of substance, the Fulfillment Centre was designed to prevent cross contamination and facilitate a seamless and secure workflow. This integrated approach ensured efficient coordination between obtaining the substances and preparing them for distribution at the Compassion Club.

DULF’s Compassion Club, operated by peers and volunteers, provided a space equipped with three injection booths, a bathroom, essential harm reduction supplies, and a counter for individuals to access substances. The space was sanctioned as an Urgent Public Health Need Site (UPHNS) (Lysyshyn, 2022) and an Overdose Prevention Site (OPS). Initially, the space was open on Mondays and Fridays for a total of 14 h, from 11:30 am to 6:50 pm. However, as DULFʼs capacity expanded, so did the operational hours of the Compassion Club. Towards the end of the program, it became a 24 h per week service, with additional opening times on Sundays and Wednesdays from 3:30 pm to 6:50 pm. Access to the space was facilitated through a doorbell monitored by volunteers, featuring a sign that read, “push here for the research study if you want to be researched,” strategically designed to prevent unintended community engagement. Two locked doors provided an “airlock” system of entry into the club itself which ensured a controlled and secure environment for members.

Criteria for membership in compassion club

To access substances from the DULF Compassion Club, individuals had to apply for membership via a local drug user group (Drug User Liberation Front, 2023b, p. 96). During this selection process, DULF mandated that drug user groups adhere to minimum safety and screening standards to connect their members with the Compassion Club. These standards included operating as a “by-and-for” group (i.e., run by drug users for drug users), maintaining an active membership list, and keeping financial records with accountability processes in place.

Furthermore, DULF stipulated that membership screening for the Compassion Club itself be conducted by both a current member of a drug user group and a DULF staff member or volunteer. The primary objective of this screening was to assess whether an individual met the minimum requirements for membership to the club. To access the DULF Compassion Club, participants had to provide ongoing and informed consent; be at least 19 years old; be a member of a Drug User Group; have access to the illegal and unregulated drug supply of one of the following substances: heroin, methamphetamine, or cocaine; and be at high risk of overdose.

Due to capacity constraints, qualified individuals were randomly selected for participation in the Compassion Club from a pool of applicants. Those who were not selected were placed on a waitlist until the clubʼs capacity increased.

Given statements made by Health Canada during DULFʼs Judicial Review regarding the effectiveness of DULFʼs screening process, it worth noting that, at baseline, 84 % (n = 39) participants used cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine daily, and 16 % (n = 8) participants used them more than once a week. Further, 88 % (n = 41) of participants reported using drugs the same day of their intake interview. Despite this, only 33 % (n = 14) of queried participants had been diagnosed with a substance use disorder.

Program activities

Obtaining substances and regulatory barriers

The optimal approach to source substances within a compassion club model hinges on obtaining pharmaceutical-grade substances from a duly licensed and regulated producer. If feasible, the Fulfillment Centre segment of the CC&FC model could be outsourced to a legitimate provider. However, this option is not attainable without a Section 56 Exemption within the confines of the existing regulatory framework for a multiplicity of reasons. This is primarily because a Section 56 Exemption is necessary to allow an organization to operate outside of laws and statues related to narcotics which prohibit the sale of narcotics in non-medicalized environments, more specifically if they lack a Drug Identification Number. The Narcotic Control Regulations (NCR) explicitly states that a scheduled narcotic drug can only be sold to licensed dealer, or to a person if they hold a Section 56 Exemption, or to a person who is a patient under professional treatment and require it for a medical condition (Narcotic Control Regulations (C.R.C., c. 1041), 2022). Similarly, Section C.01 of the Food and Drugs Regulation (FDR) also explicitly states that no manufacturer shall sell a drug in dosage form unless a Drug Identification Number has been assigned for that drug, and that no person shall sell a drug if they do not have a license under the NCR (Food and Drug Regulations (C.R.C., c. 870), 2023).

Adding to this complexity is the lack of suitable and available approved consumer drugs with Drug Identification Numbers. The Drug Product Database in Canada reveals a dearth of approved consumer drugs suitable for integration into a compassion club model. Nevertheless, and notably, IV heroin stands out as an active consumer product with a Drug Identification Number (refer to Table 1 for a list of drugs approved for use in Canada as of April 9, 2024) (Government of Canada, 2024). However, even this available formulation of heroin, as per the database, proves impractical for a compassion club due to its availability large vials (e.g., 200 mg or 5000 mg) that must be utilized at once (i.e., as 2–50 injections/shots at 0.1 g each) owing to a lack of preservative. Adding to the problem is the fact that other substitutional consumer drugs face barriers—hydromorphone, the preferred replacement opiate among healthcare providers, encounters limited acceptance among individuals using drugs as an alternative to fentanyl (British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, 2019, p. 22). Similarly, Dexedrine, the go-to replacement stimulant, sees low uptake as a substitute for methamphetamine or cocaine (Xavier et al., 2023, pp. 29–32).

Table 1. Canada drug product database.

| List of returned drug products: Cocaine | |||||||||

| Products returned by the search are listed, including their status, DIN number, name, class, total count of active ingredients and the name of one, etc. | |||||||||

| Status | DIN | Company | Product | Class | PM | Schedule | # | A.I. name | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancelled Post Market | 1962388 | SANDOZ CANADA INCORPORATED | COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE TOP SOL 40MG/ML | Human | No | Narcotic (CDSA I) | 1 | COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE | 40 MG / ML |

| Cancelled Post Market | 2004062 | SANDOZ CANADA INCORPORATED | COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE TOPICAL SOL 10% | Human | No | Narcotic (CDSA I) | 1 | COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE | 100 MG / ML |

| Dormant | 2006316 | PHARMASCIENCE INC | PMS-COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE TOPICAL SOL 4% | Human | No | Narcotic (CDSA I) | 1 | COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE | 40 MG / ML |

| Dormant | 2006308 | PHARMASCIENCE INC | PMS-COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE TOPICAL SOL 10% | Human | No | Narcotic (CDSA I) | 1 | COCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE | 100 MG / ML |

| List of returned drug products: Diacetylmorphine [Heroin] | |||||||||

| Products returned by the search are listed, including their status, DIN number, name, class, total count of active ingredients and the name of one, etc. | |||||||||

| Status | DIN | Company | Product | Class | PM | Schedule | # | A.I. name | Strength |

| Marketed | 2524996 | PHARMASCIENCE INC | DIACETYLMORPHINE HYDROCHLORIDE | Human | Yes | Narcotic (CDSA I) | 1 | DIAMORPHINE HYDROCHLORIDE | 200 MG / VIAL |

| Marketed | 2525003 | PHARMASCIENCE INC | DIACETYLMORPHINE HYDROCHLORIDE | Human | Yes | Narcotic (CDSA I) | 1 | DIAMORPHINE HYDROCHLORIDE | 5000 MG / VIAL |

| List of returned drug products: Methamphetamine (Note: Methamphetamine has no associated drug product.) | |||||||||

| Products returned by the search are listed, including their status, DIN number, name, class, total count of active ingredients and the name of one, etc. | |||||||||

| Status | DIN | Company | Product | Class | PM | Schedule | # | A.I. name | Strength |

| N/A | |||||||||

It was thus, in the absence of a Section 56 Exemption and considering drug users’ preference for substances not available as consumer goods with Drug Identification Numbers, such as cocaine, crack cocaine, methamphetamine, and smokable street down (heroin and/or fentanyl) (Xavier et al., 2023, pp. 25–39), that DULF found itself compelled to resort to the illicit market for substance sourcing. To this end, DULF’s Fulfillment Centre took on the responsibility of procuring substances from the illicit market via dark web market vendors in Canada. Upholding ethical considerations, DULF exclusively engaged with narcotic-only dark web markets, attempting to steer clear of contributing funds to negative externalities. Opting for online purchases further provided the added benefits of reducing in-person interactions and potential violence for us as purchasers, while transactions through darknet markets offered an additional layer of anonymity for vendors. This entire process involved purchases made over Tor networks, utilizing the highly encrypted Tails Operating System, and payments executed in the cryptocurrencies Bitcoin or Monero. Importantly, it is crucial to note that all DULF purchases were funded through crowdsourced or member-donated funds, with crowdsourced donations publicly posted to dispel any speculation to the contrary (Open Collective, 2023).

Substance storage

Upon receiving substances through the mail, DULFʼs administrators promptly secured them within a time-delayed vault on-site at the Fulfillment Centre. Simultaneously, the type of drug, amount of substance, and the date received were diligently logged onto an “untested” label, which was affixed to the received substance, and into a narcotic ledger (Fig. 4), which encompassed both physical and digitized records (Drug User Liberation Front, 2023b, p. 87). Every entry in the vault narcotic ledger was initialled by both administrators at the Fulfillment Centre, ensuring a robust system of accountability to address potential concerns related to theft or loss.

Access to the Fulfillment Centre vault was restricted solely to DULF administrators, further fortifying accountability measures. To mitigate risks, the vaultʼs inventory underwent regular counts by both administrators whenever it was accessed, guaranteeing the absence of theft, loss, or diversion. The same ledger meticulously documented any transfers, including those to the volunteer safe, samples removed for confirmatory testing, and samples “burnt” or discarded due to contamination. Substances, once received, and logged in the ledger, remained behind two locked doors, accessible only during inventory, testing, for packaging, or after packaging, when taken out of storage for transfer to the Compassion Club. To minimize the risk of cross-contamination, only one substance was removed from the vault at a time, ensuring a meticulous and secure process throughout.

Substance testing

Once initially logged into the vault, but before the packaging and final labelling stages, DULF initiated a crucial quality control and testing process. This testing process unfolded in two stages: first, through paper spray ionization mass spectrometry (PS-MS) testing, followed by confirmatory testing using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometry. Initially, samples were couriered to the Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project for PS-MS (Substance, 2023). Once the PS-MS results were received, indicating a substance was free of fentanyl and benzodiazepines, and its potency was known, a label with the test date, number, and result was affixed over the initial “untested” label. Simultaneously, samples were sent for secondary confirmatory testing at the University of British Columbia via UPLC-MS (Drug and Alcohol Testing Association of Canada, 2023) and NMR (Evans Ogden, 2023). Once results were received from the University of British Columbia, they were also added to the new label. While secondary confirmatory testing took additional time, it played a crucial role in allowing DULF to build confidence in the accuracy of the results obtained.

Following the completion of testing, the corresponding test codes (i.e. the test code from University of Victoria and University of British Columbia) were added to the vault Log, marking the substances as ready for the subsequent packaging and labelling phase. Itʼs important to note that substances were not made available for collection by compassion club members until confirmatory testing had taken place.

Packaging and labelling of substances

A second pivotal aspect of the harm reduction facilitated by DULF’s CC&FC was the provision of information empowering users to make informed choices about their substance use. In contrast to street purchases where consumers lack such information, substances from the DULF compassion club were packaged and labelled with detailed contents and percentage composition, determined through testing. Adopting a format akin to tobacco labelling (Government of Canada, 2023b), the packaging maintained a plain appearance featuring warnings about the highly addictive nature and impairing effects of the substances. To enhance safety and reliability, the club eventually employed tamper-resistant packaging, transparent on one side to ensure that both club members and staff could verify the correct substance and amount (Fig. 5). Drugs were packaged into 0.1 g, 0.5 g, and 1.0 g packages, with heroin only being packaged into 0.1 g and 0.5 g packages as an added preventative measure, as larger denominations could lead to over-administration of the drug.

Distribution of substances

Participants at DULF’s Compassion Club were eligible to receive a weekly allocation of up to 14 g each of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine. These substances were made available at base cost, ensuring that no profit or program fees were added. This base cost was intentionally set at the lowest possible level, reflecting the cost of goods at purchased scale (e.g. 0.1 g of methamphetamine for $1.75; 1.0 g for $17.50, and so forth).

In terms of distribution logistics, DULF’s volunteers operated from a desk with a limited inventory of substances (Fig. 6), while the excess stock remained securely stored in the volunteer safe which was stocked by DULF administrators from the fulfillment centre vault. The desk inventory was replenished throughout the day as needed. Volunteers tracked distribution via a point-of-sale system and a narcotic log similar to the log used by DULF administrators. All money collected by volunteers were meticulously counted, placed into a membership donation satchel, and sealed in a dated envelope at the end of each shift. Subsequently, administrators gathered these donations, and any potential discrepancies between daily distribution reports generated by the point-of-sale system, the volunteer narcotic log, and the petty cash log were thoroughly investigated by administrative staff.

Overdose prevention services

As previously mentioned, the DULF Compassion Club served as a sanctioned overdose prevention site (OPS) which operated under government authorization, allowing members to consume substances on-site while being supervised by honoraria-paid peers (Fig. 7). This supervision extended to substances obtained both from the illicit street market and from DULF. The OPS activities were diligently tracked by volunteers using a password protected Excel spreadsheet that indexed participant numbers, time of use, drugs used, and noted any instances of overdose or adverse impacts resulting from substance consumption. At the time of program closure, despite over one thousand consumption events, zero overdoses with naloxone administered had occurred in the space (Drug User Liberation Front, 2023a). Although DULFʼs full OPS record was seized by the police, DULFʼs one year data shows that there had been: 219 uses of DULF Heroin, 188 without use of street drugs, and no overdoses; 278 uses of DULF Cocaine, 143 without concurrent use of street drugs, and no overdoses; and 414 uses of DULF Methamphetamine, 268 without concurrent use of street drugs, and no overdoses (Drug User Liberation Front, 2023a).

In addition to keeping an index of each use of the site, CC volunteers kept a vigilant watch on participants in case of potential overdoses, and therefore were able to respond promptly and appropriately if needed. CC volunteers also took on the responsibility of maintaining a constant supply of safer injection and inhalation materials throughout the day. Additionally, volunteers ensured that injection booths were methodically sanitized after each use and prepared for subsequent use. To this end, proper disposal of injection equipment and other biohazardous materials was also a priority.

CC volunteers also underwent comprehensive training in overdose response best practices. This encompassed a range of skills, including but not limited to CPR best practices, naloxone administration, advanced overdose response techniques (involving the use of oxygen tanks, airways, bag valve masks, etc.), and defibrillator use best practices. This extensive training equipped volunteers with the necessary skills to respond effectively and promptly in case of emergencies at the CC&FC and in the surrounding community.

Program impact and significance

After a year and two months of operation, DULFʼs CC&FC faced an abrupt raid by the Vancouver Police Department that resulted in its shuttering (Vancouver Police, 2023). Nevertheless, by this time, the Compassion Club and Fulfillment Centre had served 49 individuals, with only two withdrawing from the project, and had distributed over 3000 g of drugs, valued at over $125,000, and with a street value of $250,000 had it been sold at inflated prices by organized crime. As previously mentioned, the CC&FC had also led to a statistically significant reduction in overdoses, with zero overdoses occurring under observation at DULFʼs supervised consumption site (Kalicum et al., 2024).

Despite these positive outcomes, the sudden termination of the CC&FC occurred without warning (Drug User Liberation Front, 2023d). The raid itself resulted in the seizure of all DULF computers, all localized data, as well as all of DULFʼs substances and the rest of its equipment. Additionally, both founders of the CC&FC had their homes raided and have been charged under the CDSA section 5(2) Possession with Intention to Traffic, with each charge carrying a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. While the discussion of these matters is beyond the scope of this paper, the charges could have significant downstream ramifications, including raising questions about whether the potential for severe jail time could deter others from establishing similar programs to DULF’s CC&FC, even clandestinely.

Nevertheless, and while reviewing the programʼs success at length remains beyond the scope of this paper, itʼs essential to acknowledge its notable achievements. In post-raid media, the projects’ successes were depicted by participants themselves. For instance, a participant noted:

DULF was a ray of hope while it was there, and (the shutdown) has really crushed a lot of people, […] If you’re not going to help us, then get out of the way and let us help ourselves because we’re f***ing dying. […] It was a real community-like feeling environment, […] where I felt unconditionally safe, where I could go and I could be warm (Culbert & DeRosa, 2023).

While another added:

[The Compassion Club] was essential for survival. You know, without DULF, it’s kind of Russian roulette, going and trying to score on the street nowadays (Culbert & DeRosa, 2023).

Five participants further added the following in a public letter upon hearing of DULF’s our arrest:

The Compassion Club continued with full transparency. At the one-year mark, a formal evaluation proved what we knew all along, and what government failed and continues to fail to recognize: Low-barrier, community-led access to a regulated drug supply equals improved health and social outcomes including reduced overdoses, deaths, hospitalizations, violence, and negative police interactions. Not one overdose was known to be caused by DULF’s supply (Anonymous Compassion Club Members, 2023).

Lessons learnt

Since the arrests, progress toward establishing a de-medicalized safer supply has stalled, while the overdose crisis continues to devastate Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside unabated. Despite requiring only minimal adjustments to the initial structure of DULF’s program, expanding operating hours, accommodating more participants, and bolstering the substance inventory proved beneficial in offering more effective assistance to participants. Nevertheless, in an ideal scenario, the program would have encompassed a larger participant pool, operated seven days a week with a guaranteed supply chain, had better security measures, and potentially included a twenty-four hour, and seven day per week access option. To this end, DULF would have greatly benefited from explicit legal sanctioning, which, in addition to ensuring a stable supply chain, could have prevented the arrests of two of its cofounders, the subsequent shutdown of the program, data loss, and invasion of privacy. In this regard, exercising more discretion, such as maintaining a lower profile in the media, could have helped avoid arrest. Finally, several scientific refinements could have enhanced the evaluative framework. These include ensuring coherence in follow-up evaluations, expanding program capacity (which requires a larger inventory), maintaining a control population, and utilizing metrics beyond self-reporting.

Discussion

This case study underscores the feasibility of a community-based intervention in addressing the current public health crisis, revealing that drug users themselves can orchestrate a program aimed at safeguarding their communities. The DULF CC&FC serves as another compelling instance of drug users mobilizing to benefit their communities (Latkin & Friedman, 2012), operating several steps ahead of health bureaucracies (Kerr et al., 2001). In line with previous evaluations of drug user-run interventions, including studies on the activities of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (Jozaghi & Yake, 2020), and unsanctioned and illegal overdose prevention sites in Vancouver (Kerr et al., 2004), Toronto (Foreman-Mackey et al., 2019), and the United Kingdom (Parkin & Coomber, 2009), our findings demonstrate positive outcomes associated with engagement by drug users with drug user run programming.

While DULFʼs CC&FC shares similarities with other “compassion” or “buyers” clubs, such as those focused on providing access to medicinal cannabis (Kent, 1999) or antiretroviral therapy for HIV disease (Rhodes & Van De Pas, 2022), it represents a highly innovative form of safe supply programming. DULFʼs program also remains disjunct from other medical models as discussed in a recent evidence review insofar as it does not require a prescriber, daily dispensation, witnessed use, etc. (Ledlie et al., 2024). To this end, the distinction between a non-medicalized and medicalized supply of narcotics should not be drawn at its legality as suggested by Nielsen, Stowe, and Ritter when they state, “[in] contrast to the challenges of a nonmedical model, the medical models are legal” (Nielsen et al., 2024), and instead, the distinction should be focused on the imposition or lack of supervisory medical controls. Ultimately, there appears to be no evidence specific to interventions focused on ensuring access to a non-prescription safe supply of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine, aside from what has been generated by those involved in DULFʼs program itself. The lack of existing research on the impact of a safer drug supply that bypasses the medical system underscores the importance of contextualizing this work within the broader landscape of safer supply initiatives, their successes, and limitations (Penn et al., 2023). These initiatives have often faced challenges such as a lack of viable licit drug options (Karamouzian et al., 2023), severely limited capacity (Karamouzian et al., 2023), and ethical concerns among healthcare professionals (Cooper, 2023) (Lamb, 2021). With this said, an unpublished qualitative investigation revealed that the DULF CC was more culturally acceptable to participants than traditional prescriber based models (Bowles et al., n.d.).

As highlighted during the programʼs inception, the DULF CC&FC model significantly magnified the potential impact of drug checking as a harm reduction service by strategically testing substances at a higher point in the distribution chain (Lysyshyn, 2021). Notably, at the conclusion of the program, there were no reported overdoses attributed to DULFʼs drugs that necessitated naloxone administration, and subsequent evaluation work has demonstrated that DULF CC members had a significantly reduced risk of non-fatal overdose (Kalicum et al., 2024). While it’s important to heed recent commentary, such as that from Nielsen et al. (2024), cautioning against viewing DULF’s program as a “silver bullet” absent further evidence, it is necessary to highlight the strengths of the initiative. Particularly, when compared to existing safer-supply initiatives extensively reviewed in recent literature by Ledlie et al. (2024), DULFʼs approach diverged from traditional medicalized and prescriber-based models. By doing so, it circumvented numerous limitations inherent in such models, such as the requirement for witnessed medication dispensation, lack of medication carries, the necessity for participant urinalysis or blood testing, medically supervised titration, stigma associated with the medical system, and high program administration costs, among others.

In essence, DULF successfully surmounted challenges faced by other programs, including overcoming regulatory hurdles associated with initiatives explicitly providing licit supply (Bonn et al., 2021). This essay not only demonstrates the viability of compassion clubs but also illuminates how these clubs can address gaps and limitations inherent in existing safe supply programs (Bonn et al., 2021). However, persistent regulatory issues, such as the need to expand the range of drugs accessible for compassion club programs through Health Canada sanctioning, remain significant hurdles. Consequently, essential reforms are needed, including amendments to the Special Access Program, the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, and the Food and Drugs Act, which currently impede the implementation of Compassion Clubs as a solution to Canada’s public health crisis (Bonn et al., 2021). Additionally, broader application and approval of Section 56 Exemptions, or amendments to the Food and Drugs Act and related regulations, including the Narcotics Control Regulations, are imperative.

Conclusions

The present essay set out to document the inception, structure, and operations of the DULFʼs Compassion Club and Fulfillment Centre during its operational phase. The essay investigated how the projectʼs approach ensured person-centred, quality care for its membership. By strategically testing substances at a higher point in the distribution chain, the non-medicalized compassion club framework introduced by DULF emerges as an innovative strategy to regulate the illicit drug market. This approach not only overcame obstacles faced by existing programs but also demonstrated the feasibility of compassion clubs as a solution to British Columbiaʼs ongoing health crisis. Nevertheless, it remains imperative to address persistent regulatory challenges and advocate for reforms. In doing so, the government could pave the way for a more comprehensive and person-centred approach to supporting individuals who use drugs, contributing to positive outcomes in both health and social domains.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Eris Nyx: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jeremy Kalicum: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

This paper developed on the stolen land of the Coast Salish Peoples, including the territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl ̓ ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. The DULF would also like to extend special thanks to our Indigenous Advisory Council; the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users; the Western Aboriginal Harm Reduction Society; the BC Association of People on Opiate Maintenance; the Coalition of Peers Dismantling the Drug War; all the other by-and-for drug user groups who have helped us in our fight; as well as all of those who have come before us.

References

- Anonymous Compassion Club Members, 2023Anonymous Compassion Club Members. (2023). Letter from five members of DULF’s compassion club. https://www.drugdatadecoded.ca/p/letter-from-five-members-of-dulfs

.

Google Scholar Bowles et al., Unpublished Results.

Bowles, J.; Kalicum, J.; Nyx, E., Qualitative findings from North America’s first drug. compassion club (Unpublished Results).

Google ScholarBC Coroners Service Death Review Panel, 2023

BC Coroners Service Death Review Panel. (2023). BC coroners service death review panel: an urgent response to a continuing crisis [Report to the Chief Coroner of British Columbia]. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/an_urgent_response_to_a_continuing_crisis_report.pdf

.

Google ScholarBC Ministry of Health 2016

BC Ministry of Health. (2016). Provincial health officer declares public health emergency. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2016HLTH0026-000568

.

Google ScholarBC Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, 2023

BC Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions. (2023). Escalated drug-poisoning response actions. https://news.gov.bc.ca/factsheets/escalated-drug-poisoning-response-actions-1

.

Google ScholarBonn et al., 2021

Bonn, M., Touesnard, N., Cheng, B., Pugliese, M., & Comeau, E. (2021). Securing safe supply during COVID-19 and beyond: scoping review and knowledge mobilization review and knowledge mobilization. https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2323&context=scholarly_works

.

Google ScholarBritish Columbia Centre on Substance Use 2019

British Columbia Centre on Substance Use. (2019). Heroin compassion clubs. https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Report-Heroin-Compassion-Clubs.pdf

.

Google ScholarCanadian Association of People who Use Drugs 2019

Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs. (2019). Safe supply concept document. https://www.capud.ca/capud-resources/safe-supply-projects

.

Google ScholarCenters for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Multiple cause of death, 1999–2020 results drug overdose deaths of US residents by year 1999–2017 deaths occurring through 2020. CDC WONDER Online Database. https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/saved/D77/D72F580

.

D. Ciccarone

The triple wave epidemic: Supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis

International Journal of Drug Policy, 71 (2019), pp. 183-188, 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.010View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle ScholarCloud, 2021

Crack Cloud (Director). (2021). Overdose awareness rally DTES 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJVd7R18LeY

.

Google ScholarCole Schisler, 2024

Cole Schisler. (2024). B.C. brings in new addictions care advisor as premier questions advice of Dr. Bonnie Henry. https://vancouver.citynews.ca/2024/06/05/bc-drug-safe-supply-eby-henry/

.

Cooper, R. (2023). Free government funded hydromorphone letter with cover letter. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/jnezr30uaj9qu5jwvnk1v/Free-government-funded-hydromorphone-Letter-with-Cover-Letter-Sep-21-2023-1-1.pdf?rlkey=jeifhqy4rx199l4ozfumtwdhe&dl=0

.

Google ScholarCoroners Service, 2023

BC Coroners Service. (2023). Unregulated drug deaths—summary. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNDI2ZTc0YzUtNDA2MS00NTkwLWFmYzctNjc2NjAzNWZmZmZmIiwidCI6IjZmZGI1MjAwLTNkMGQtNGE4YS1iMDM2LWQzNjg1ZTM1OWFkYyJ9

.

Google ScholarCoroners Service, 2024

BC Coroners Service. (2024). Unregulated drug deaths—summary. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNjRhYTBhNmUtMDBmNy00YWYxLTkzMTMtMDI5NmZiM2Y1MzhmIiwidCI6IjZmZGI1MjAwLTNkMGQtNGE4YS1iMDM2LWQzNjg1ZTM1OWFkYyJ9

.

Google ScholarCrowe et al., 2011

S. Crowe, K. Cresswell, A. Robertson, G. Huby, A. Avery, A. Sheikh

The case study approach

BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11 (1) (2011), p. 100, 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100View in ScopusGoogle ScholarCulbert and DeRosa, 2023

Culbert, L., & DeRosa, K. (2023). This Vancouver compassion club was saving lives. Then things got political. https://vancouversun.com/health/local-health/vancouver-drug-users-liberation-front-politics

.

Google ScholarDrug and Alcohol Testing Association of Canada, 2023

Drug and Alcohol Testing Association of Canada. (2023,). UBC lab testing new portable drug-checking device. https://datac.ca/ubc-lab-testing-new-portable-drug-checking-device/

.

Google ScholarDrug User Liberation Front 2023b

Drug User Liberation Front. (2023). The D.U.L.F. and V.A.N.D.U. Evaluative compassion club and fulfillment centre framework. https://www.dulf.ca/framework

.

Google ScholarDrug User Liberation Front, 2021a

Drug User Liberation Front. (2021). Section 56(I) exemption to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) required to ensure the equitable application of public health protections to vulnerable Canadians. https://www.dulf.ca/sect56

.

Google ScholarDrug User Liberation Front, 2021b

Drug User Liberation Front. (2021). Substance use and addictions program grant proposal for the DULF fulfillment centre and compassion club pilot project.

Google ScholarDrug User Liberation Front, 2023a

Drug User Liberation Front. (2023). DULF CC overdose prevention site log.

Google ScholarDrug User Liberation Front, 2023c

Drug User Liberation Front. (2023). About the dope on arrival giveaway program. https://www.dulf.ca/doa

.

Google ScholarDrug User Liberation Front, 2023d

Drug User Liberation Front. (2023). DULF CC preliminary findings. https://www.dulf.ca/cc-preliminary-findings

.

Google ScholarEvans Ogden, 2023

Evans Ogden, L. (2023). Modernizing testing for harm reduction in a toxic drug supply. https://www.cheminst.ca/magazine/article/modernizing-testing-for-harm-reduction-in-a-toxic-drug-supply/

.

Google ScholarFood and Drug Regulations (C.R.C., c. 870), 2023

Food and Drug Regulations (C.R.C., c. 870) (2023). https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/c.r.c.,_c._870/FullText.html

.

Google ScholarForeman-Mackey et al., 2019

A. Foreman-Mackey, A.M. Bayoumi, M. Miskovic, G. Kolla, C. Strike

‘It’s our safe sanctuary’: Experiences of using an unsanctioned overdose prevention site in Toronto, Ontario

International Journal of Drug Policy, 73 (2019), pp. 135-140, 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.09.019View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle ScholarGovernment of Canada, 2023a

Government of Canada. (2023). Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/maps.html

.

Google ScholarGovernment of Canada, 2023b

Government of Canada. (2023). Tobacco product labelling. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco/legislation/tobacco-product-labelling.html

.

Google ScholarGovernment of Canada, 2024

Government of Canada. (2024). Drug product database. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-product-database.html

.

Harmony, P. (2021). Movements act to end overdoses from tainted drugs. https://www.workers.org/2021/04/56024/

.

Google ScholarJozaghi and Yake, 2020

E. Jozaghi, K. Yake

Two decades of activism, social justice, and public health civil disobedience: VANDU

Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111 (1) (2020), pp. 143-144, 10.17269/s41997-019-00287-0View in ScopusGoogle ScholarKalicum et al., 2024

J. Kalicum, E. Nyx, M.C. Kennedy, T. Kerr

The impact of an unsanctioned compassion club on non-fatal overdose

International Journal of Drug Policy, (2024)

Epub ahead of print

Google ScholarKaramouzian et al., 2023

M. Karamouzian, B. Rafat, G. Kolla, K. Urbanoski, K. Atkinson, G. Bardwell, M. Bonn, N. Touesnard, N. Henderson, J. Bowles, J. Boyd, C. Brunelle, J. Eeuwes, J. Fikowski, T. Gomes, A. Guta, E. Hyshka, A. Ivsins, M.C. Kennedy, …, D. Werb

Challenges of implementing safer supply programs in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis

International Journal of Drug Policy, 120 (2023), Article 104157, 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104157View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle ScholarKent, 1999

H. Kent

A step ahead of the law, “Compassion Club” sells marijuana to patients referred by MDs

CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne, 161 (8) (1999), p. 1024

View in ScopusGoogle ScholarKerr et al., 2001

Kerr, T., Douglas, D., Peeace, W., Pierre, A., & Wood, E. (2001). Responding to an Emergency: Education, advocacy and community care by a peer-driven organization of drug users. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/sc-hc/H39-4-61-2001-eng.pdf

.

Google ScholarKerr et al., 2004

T. Kerr, M. Oleson, E. Wood

Harm-reduction activism: A case study of an unsanctioned user-run safe injection site

Canadian HIV/AIDS Policy & Law Review, 9 (2) (2004), pp. 13-19

View in ScopusGoogle ScholarKerr et al., 2006

T. Kerr, W. Small, W. Peeace, D. Douglas, A. Pierre, E. Wood

Harm reduction by a “user-run” organization: A case study of the Vancouver area network of drug users (VANDU)

International Journal of Drug Policy, 17 (2) (2006), pp. 61-69, 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.01.003View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle ScholarLamb, 2021

Lamb, V. (2021). As a doctor, I was taught ‘first do no harm.’ That’s why I have concerns with the so-called ‘safe supply’ of drugs. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-as-a-doctor-i-was-taught-first-do-no-harm-thats-why-i-have-a-problem/

.

Google ScholarLatkin and Friedman, 2012

C. Latkin, S. Friedman

Drug use research: Drug users as subjects or agents of change

Substance Use & Misuse, 47 (5) (2012), pp. 598-599, 10.3109/10826084.2012.644177View in ScopusGoogle ScholarLedlie et al., 2024

S. Ledlie, R. Garg, C. Cheng, G. Kolla, T. Antoniou, Z. Bouck, T. Gomes

Prescribed safer opioid supply: A scoping review of the evidence

International Journal of Drug Policy, 125 (2024), Article 104339, 10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104339View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle ScholarLysyshyn, 2021

Lysyshyn, M. (2021). Letter of Support for DULF Section 56 Exemption. https://www.dulf.ca/_files/ugd/fe034c_1efb5bffe71c440780d2a4e539ebb122.pdf?index=true

.

Lysyshyn, M. (2022). B.C. medical health officer distributed drug checking site—agreement letter [Personal communication].

Darren Major. (2024). Ottawa approves B.C.’s request to recriminalize use of illicit drugs in public spaces. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/federal-government-approves-recriminalization-use-drugs-public-british-columbia-1.7196765

.

Moakley, P. (2021). The ‘Safe Supply’ movement aims to curb drug deaths linked to the opioid crisis. https://time.com/6108812/drug-deaths-safe-supply-opioids/

.

Google ScholarNarcotic Control Regulations (C.R.C., c. 1041), 2022

Narcotic Control Regulations (C.R.C., c. 1041) (2022). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._1041/FullText.html

.

Google ScholarNational Vital Statistic System 2024

National Vital Statistic System. (2024). Provisional drug overdose death counts. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

.

Google ScholarNguemeni Tiako et al., 2022

M.J. Nguemeni Tiako, J. Netherland, H. Hansen, M. Jauffret-Roustide

Drug overdose epidemic colliding with COVID-19: What the United States can learn from France

American Journal of Public Health, 112 (S2) (2022), pp. S128-S132, 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306763

Google ScholarNielsen et al., 2024

S. Nielsen, M.J. Stowe, A. Ritter

In pursuit of safer supply: An emerging evidence base for medical and nonmedical models

International Journal of Drug Policy, 126 (2024), Article 104365, 10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104365View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle ScholarNyx and Kalicum, 2019

Nyx, E., & Kalicum, J. (2019). Safe Supply 2019 Conference Agenda. Safe Supply 2019.

Nyx, E. (Director). (2021). International Overdose Awareness Day August 31 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NiyHGaf7eXE

.

Google ScholarOpen Collective, 2023

Open Collective. (2023). Open collective: DULF. https://opencollective.com/dulf

.

Google ScholarParkin and Coomber, 2009

S. Parkin, R. Coomber

Informal ‘Sorter’ Houses: A qualitative insight of the ‘shooting gallery’ phenomenon in a UK setting

Health & Place, 15 (4) (2009), pp. 981-989, 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.03.004View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle ScholarPenington Institute, 2022

Penington Institute. (2022). Facts & Stats. https://www.overdoseday.com/facts-stats/

.

Google ScholarPenn et al., 2023

Penn, R., Kalda, R., & Holtom, A. (2023). Prescribed safer supply programs: Emerging evidence. https://www.nss-aps.ca/sites/default/files/resources/2023-12-11-PSSEvidenceBrief.pdf

.

Pot TV (Director). (2021). Free drugs outside police station for golden ticket holders. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7fPVYFieEW4

.

Google ScholarRhodes and Van De Pas, 2022

N. Rhodes, R. Van De Pas

Mapping buyer’s clubs; what role do they play in achieving equitable access to medicines?

Global Public Health, 17 (9) (2022), pp. 1842-1853, 10.1080/17441692.2021.1959940View in ScopusGoogle ScholarSubstance 2023

Substance. (2023). Substance drug checking. https://substance.uvic.ca/

.

Google ScholarUS Census Bureau, 2024

US Census Bureau. (2024). US population by month. https://www.multpl.com/united-states-population/table/by-month

.

Google ScholarVancouver Police, 2023

Vancouver Police. (2023). VPD executes search warrants in downtown eastside drug investigation. https://vpd.ca/news/2023/10/26/vpd-executes-search-warrants-in-downtown-eastside-drug-investigation/

.

Google ScholarXavier et al., 2023

J. Xavier, J. Buxton, P. McGreevy, J. McDougall, J. Lamb

Substance use patterns and safer supply preferences among people who use drugs in British Columbia

BC Centre for Disease Control (2023)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.