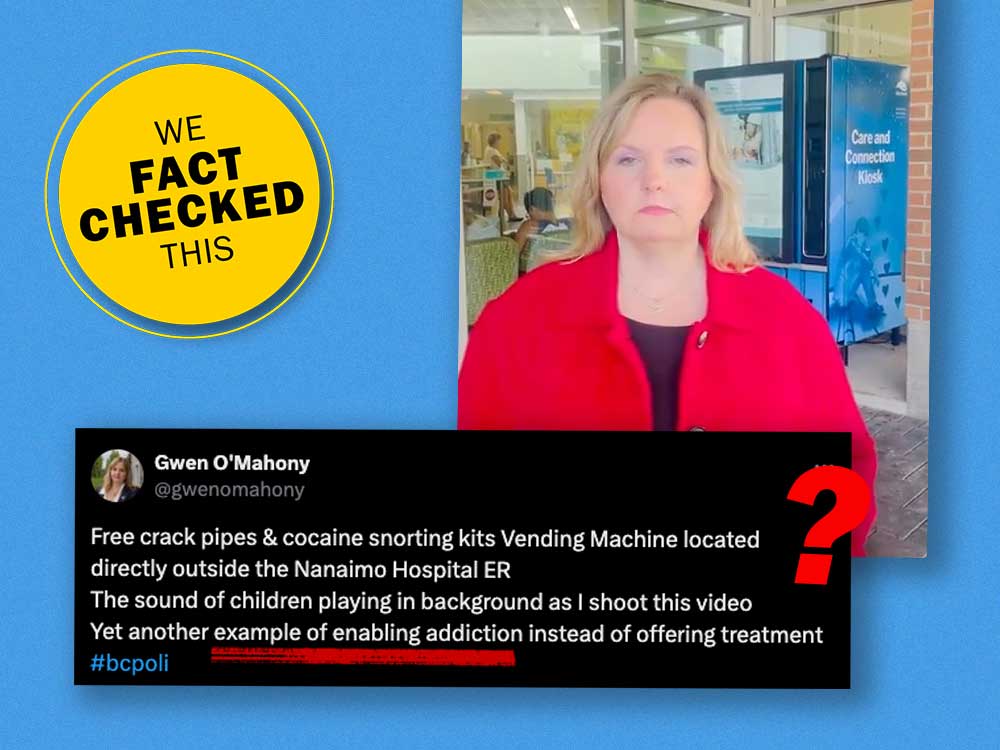

– From The Tyee – Gwen O’Mahony’s viral video makes bold claims. Do experts agree? A Tyee election report. Read the full article directly from the source

Michelle Gamage is The Tyee’s health reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative

“Let’s go get a free crack pipe and cocaine smoking kit,” says Conservative Party of BC candidate Gwen O’Mahony, looking stonily at the camera.

O’Mahony, who is running in the new Nanaimo-Lantzville riding, is the former NDP MLA for Chilliwack-Hope. According to her Conservative candidate page, she left the NDP after calling for trans women to be banned from women’s sports and prisons, and after the NDP said it would support decriminalization of personal amounts of unregulated substances.

Banning trans women from sports is not a policy supported by the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport, as it discriminates against trans athletes.

In a video posted to X on Aug. 26, O’Mahony accesses a free vending machine that dispenses harm reduction supplies at the entrance to the Nanaimo hospital’s emergency department.

She selects a “snorting kit” on the touch screen, which dispenses three paper straws and six alcohol swabs in a nondescript yellow envelope.

“Next we can learn how to snort cocaine with this informational video,” she says. The camera zooms in on the screen, which reads, “All supplies are for personal use and should not be shared with others. Viruses and bacteria can remain on supplies and can pass infections when shared.”

The video cuts to O’Mahony holding three envelopes, which she says are a crack inhalation kit and a snorting kit.

“Unfortunately the crack pipes were out, which is no surprise because crack pipes can be traded for drugs,” O’Mahony says.

In her post on X, O’Mahony says the vending machine is “enabling addiction instead of offering treatment.”

The day after the video was posted, Conservative Party of BC Leader John Rustad called the vending machine “appalling and irresponsible.”

The BC NDP responded by committing to reviewing all ways harm reduction supplies are handed out “that don’t involve direct contact between a service provider and somebody struggling with addiction,” according to reporting by CityNews.

This comes at a time when the unregulated drug supply is so toxic that more than six people die from it every day in the province, according to the BC Coroners Service. More than 14,500 people have died in B.C. since a public health emergency was declared in April 2016 in response to rising toxic drug deaths.

The toxicity of the unregulated drug supply is largely driven by the synthetic opioid fentanyl and its analogues. A few grains of fentanyl can kill a person, and people who buy unregulated substances don’t always know what substance they are buying and at what concentration.

Fentanyl was involved in 85 per cent of all toxic drug deaths in B.C. in 2023 and 83 per cent of deaths so far in 2024, according to the BC Coroners Service. The analogue carfentanil, which is 100 times more powerful than fentanyl, was involved in 15 and 17 per cent of fatalities, respectively.

A lot of policies and practices in place in B.C. are working to prevent toxic drug deaths, ranging from services that test drugs to empower people to know what they are taking, to letting them use drugs under the supervision of a health-care worker who can intervene if a person overdoses, to services that allow people to go through detox at home or access culturally appropriate treatment beds for First Nations peoples.

The BC NDP also expanded safer supply programs, where people who are at high risk of overdose are prescribed opioids or stimulants to reduce their reliance on the toxic unregulated supply; started a pilot program to decriminalize small amounts of meth, cocaine and heroin; and regularly opens new treatment beds.

In Alberta, under the United Conservative Party, the province has focused on treatment, limited the number of supervised consumption sites and avoided safer supply programs.

Overdose deaths have risen in both provinces.

In this article, we’ll focus on Conservative critiques of harm reduction supplies.

The Tyee asked the Conservative Party of BC for an opportunity to speak with O’Mahony about her reasons for posting the video and her concerns related to harm reduction. The party did not respond to our request.

We spoke with experts to evaluate the claims made by Conservatives about harm reduction and substance use, and to unpack how the Conservative approach to harm reduction could affect people who use drugs, considered a highly vulnerable population, if implemented.

THE CLAIM: Harm reduction supplies are traded for drugs.

FACT CHECK: Harm reduction supplies such as glass pipes, condoms and naloxone kits are widely available for free across the province, says Mark Haden, a University of British Columbia adjunct professor in the faculty of medicine, at the school of population and public health.

“How would you trade something that is given away for free for something that people want to make money on? It’s theoretically possible but hard to imagine how that would work.”

Harm reduction includes a range of evidence-informed services and strategies related to substance use and sexual activity and can help prevent HIV, hepatitis C, illness, infection and overdose, according to the BC Centre for Disease Control. The World Health Organization has recommended distributing free, sterile needles to reduce viral transmission for 30 years.

The first needle exchange opened in Vancouver in 1989. It was replaced by a free needle distribution program in 2002.

THE CLAIM: Harm reduction enables addiction.

FACT CHECK: Access to harm reduction services increases a person’s likelihood of seeking treatment and reducing or stopping drug use.

The claim that harm reduction enables addiction was ruled out decades ago, says Thomas Kerr, a professor and head of the division of social medicine in the department of medicine at the University of British Columbia and director of research with the BC Centre on Substance Use.

As examples, he points to research done at Vancouver’s Insite, which was North America’s first supervised injection site.

After Insite opened there was a 30 per cent increase in people using detoxification services and an increase in the number of people going into treatment and stopping drug use. Having a place to inject drugs without risk of arrest did not negatively impact how likely someone was to seek treatment.

This isn’t the first time Conservative politicians have tried to discredit and close down harm reduction services, Kerr notes.

A decade ago Stephen Harper’s government tried to shut down Insite. The resulting court case went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, where there was a unanimous ruling that closing Insite would violate people’s Charter rights.

Pierre Poilievre was an MP at the time and was part of the “humiliating” defeat, yet “here they are, over a decade later, acting as if that process never happened,” Kerr said.

THE CLAIM: If a person who uses drugs can access harm reduction services, they will not want to seek treatment.

FACT CHECK: Harm reduction services and treatment are not opposed to one another, Haden says. Instead, they’re part of the same continuum of care that also includes opioid agonist therapy, prescribed safer supply, community-based treatment and evidence-based treatment programs.

Haden compares the two to medical services for a pregnant person and medical services for a newborn and parent: similar, but with different emphasises and milestones. And, ideally, both readily available.

“If you don’t provide harm reduction services, people die, and dead people don’t seek treatment,” Haden said.

Everyone working in harm reduction or studying substance use agrees a full continuum of evidence-based services from harm reduction to abstinence-based programming is needed, Kerr says.

THE CLAIM: A hospital entrance is an inappropriate place to locate a low-barrier vending machine distributing harm reduction supplies.

FACT CHECK: “Hospitals have been dispensing harm reduction supplies for a very, very long time without significant incidents. We have experience with this type of service delivery and, as much as O’Mahony would like to stoke fear and get people alarmed about these things, there’s no basis for it,” Kerr said.

“A harm reduction supply distribution system outside a hospital is not a threat to children. It doesn’t undermine the quality of care being offered in the hospital. It doesn’t impede access to non-substance users,” he added.

B.C. has been distributing harm reduction supplies for injecting drugs for 35 years, and harm reduction supplies for safer sex for 13 years.

This long history of harm reduction is credited with B.C.’s low HIV and hepatitis C rates among people who use drugs.

Virus transmission was a big concern in the late 1990s in B.C. In 1997 the chief medical health officer for the Vancouver-Richmond Health Board declared a public health emergency in response to increasing hepatitis A, B and C and HIV infections, as well as a rise in overdose deaths. Insite was similarly opened 20 years ago to reduce the spread of HIV-AIDS and hepatitis C by providing people with access to harm reduction supplies such as sterile injecting kits.

Widespread access to sterile injection equipment is “one of the reasons we don’t have HIV epidemics among our population of people who inject drugs [today],” said Gillian Kolla, assistant professor of population health and applied health sciences at Memorial University of Newfoundland, and collaborating scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria.

“The distribution of sterile injection equipment has been a World Health Organization priority intervention to prevent HIV for 30 years. These are incredibly well-established, well-researched, well-documented public health interventions,” Kolla said.

Providing harm reduction supplies is also good fiscal policy, Kolla said.

HIV and hepatitis C are no longer life-threatening diseases as long as you can access treatment. Hepatitis C can be cured within two to three months of treatment. HIV treatment is “expensive and needs to be taken for life,” she said.

The best way to save public health costs is to prevent transmission in the first place. One 2009 study of Insite calculated that its harm reduction services had prevented around 35 new cases of HIV and three deaths per year, which created a societal benefit of $6 million per year after the program costs were taken into account.

THE CLAIM: Harm reduction should be available only in face-to-face interactions.

Fact Checked: Four Claims on Drug Deaths

FACT CHECK: Vending machines increase access to harm reduction supplies because anyone can use them, according to Kerr.

People who use drugs experience a lot of stigma, discrimination and criminalization in our society, and that creates barriers for people who want to access harm reduction services because they have to identify themselves as a drug user to do so, Kerr says.

Distributing harm reduction supplies face to face increases the opportunities to engage someone in care, which can be as simple as having someone know your name and getting to see you regularly, or it can be the first step in introducing someone to a counsellor, or a nurse who can help with wound care, Haden says.

This is the first step in providing wraparound services and increases a person’s likelihood of continuing to engage in health-care services.

But while face-to-face interactions can be valuable, they don’t negate the benefit of more discreet services, Kerr says.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.