No.

by dustin godfrey – The Bind – Read the original source article here

Dec 06, 2024

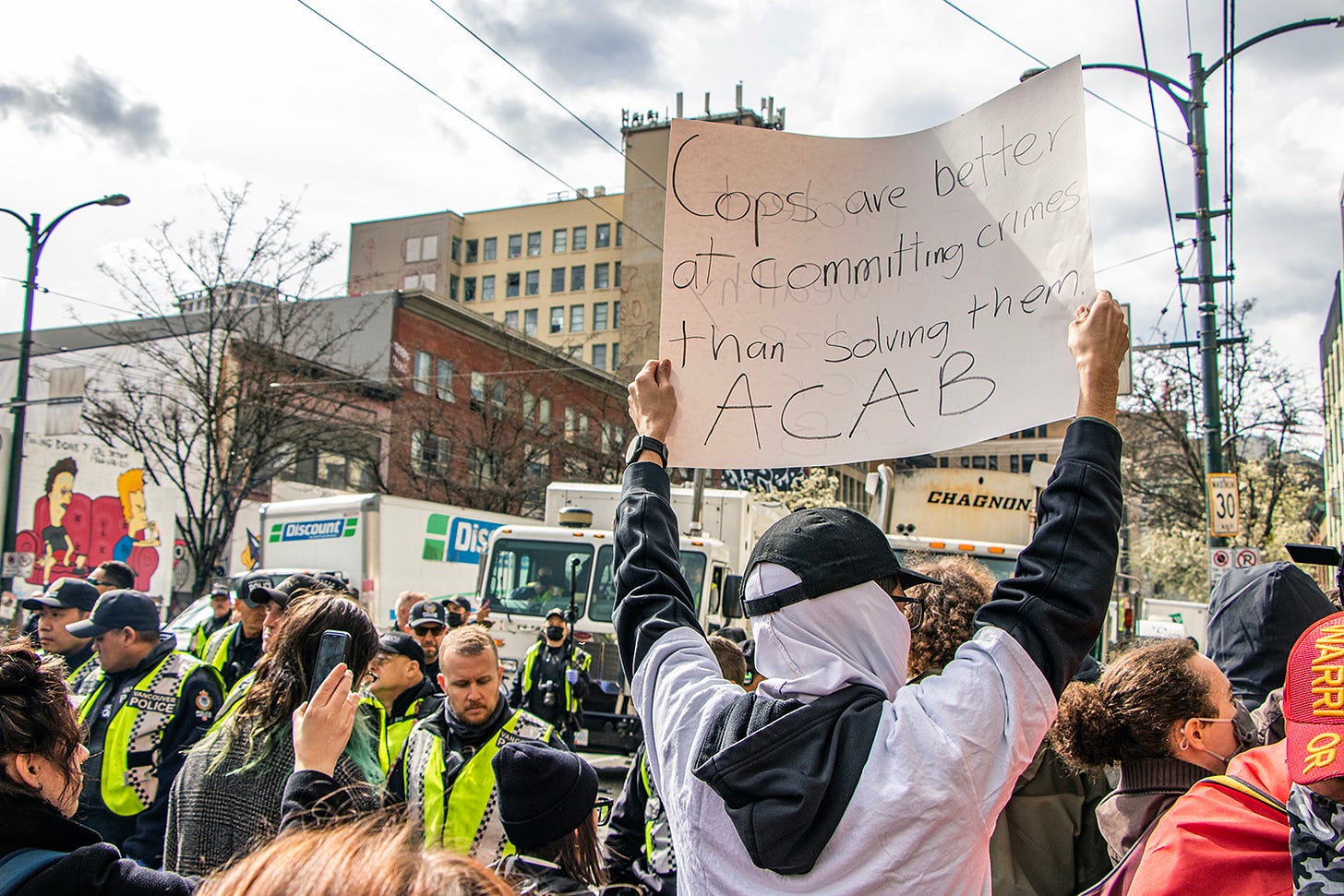

VPD displace people living in the Downtown Eastside in April 2023.

Police chiefs in Canada say they no longer support decriminalization, but a longtime Vancouver drug policy analyst says we shouldn’t take them at their word that they ever did.

The BC NDP and federal Liberal governments leaned on support from the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police and its provincial counterpart, the BC Association of Chiefs of Police, in implementing a “decriminalization” pilot that started in early 2023 and was intended to run three years.

The CACP issued a report in July 2020 stating its support for “decriminalization” of drugs for personal possession.

The organization even reaffirmed its support for decriminalization in a presentation to the federal parliament’s health committee as recently as April this year.

Thanks for reading the bind! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Reform as obstruction

But Karen Ward, a policy analyst in the Downtown Eastside, said she never believed they actually supported decriminalization, but rather that their support was an obstruction of change.

“It was an exploitative move, and it was interesting to note that they started suddenly supporting things in the summer of 2020, during the George Floyd uprisings,” Ward said.

By claiming support for decriminalization, Ward said, the chiefs of police effectively took the steam out of movements to defund the police, by focusing instead on reform and maintaining their role in drug policy.

By becoming willing participants in what was ostensibly a shift away from criminalization, police could play the part of reasonable incrementalists, rather than reactionaries with a vested interest in opposing change.

And as a result, any push for decriminalization, Ward said, “became watered down to the point of an empty gesture.”

Ward noted, for instance, that the exemption excluded those under the age of 19, leaving young drug users vulnerable to arrest and criminal charges.

When the federal government approved BC’s request for an exemption from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, it limited the removal of criminal penalties to adults carrying a cumulative 2.5 grams or less of only a handful of substances.

This was a reduction from the 4.5g requested by the BC government, following an objection from the BCACP.

Lowered thresholds

Instead, the organization proposed a limit of just 1g in a position paper that appears to have been removed from the CACP website, where it was previously hosted, but which has been preserved through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

This is despite that same report stating that the average threshold for other countries that have decriminalized drug possession is 4g, which it acknowledged to be a “gross under-estimation” because it only counted thresholds for heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine and excluded thresholds for other drugs.

It also notes that a number of countries didn’t include thresholds for meth or listed the threshold as a “day’s supply” rather than a fixed weight, further reducing that average.

And it excluded Colombia as “an extreme outlier, which would have skewed the average upward.”

Despite this, the paper still stated that the 4.5g threshold — significantly closer to the conservative estimate of 4g as an international average than the 1g limit proposed by the organization, or even the 2.5g limit the government landed on — “is not consistent with other countries or in the best interest of a public health model.”

The paper dismisses self-reported drug use trends as “not a strong evidence base to establish a drug possession threshold,” and suggested the now-defunct Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions’ inclusion of “social supply” — that is, buying enough to share with others without any profit involved — to meet the definition of trafficking and to fall outside the scope of a simple possession exemption.

The 4.5g limit proposed by the BC government itself was already far lower than the 18g limit suggested by the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users and backed by the BC Health Coalition.

And the BCACP’s suggestion would have maintained a wide discretion for police to seize people’s drugs, with the organization saying its average seizures varied from 1.3g in the RCMP North District up to 1.9g in Vancouver and Abbotsford — all well above the 1g threshold they proposed.

No systemic change

Throughout the conversation on decriminalization, advocates have insisted that there needs to be an increase in services, that decriminalization alone is not sufficient.

Moreover, they have argued that it should be paired with a reduction in police funding — that real decriminalization would remove resources from an agency that commits drug users to criminalization and turn those resources over to services that help lift people out of cycles of poverty, trauma, and criminalization.

But when police spoke of decriminalization, even as they argued for an increase in services, they made clear that they still saw police as a key agency in drug policy, and that they didn’t believe decriminalization should, in any way, reduce police budgets.

“A decriminalization or diversion model will not provide any opportunity for police agencies to reduce their operating budgets or staffing,” the report reads.

“Some have suggested that decriminalization would free up police officer time and budgets could be reallocated to other priorities; however, police agencies must continue to resource drug enforcement units dedicated to disrupting the illicit drug markets.”

Indeed, since then, the Vancouver Police Department’s budget has grown a third from $341 million in 2021 to a proposed $453 million next year. That fell $13 million short of the department’s ask, to which chief Adam Palmer cried poverty, calling the $1.24-million-a-day fund, which would still account for a full quarter of the city’s non-utility operating budget, a “keep the lights on” budget.

In fact, while other public organizations have been pushed to find areas to reduce spending in multiple levels of government in recent years, Palmer told the board that if he didn’t get his requested protest budget, rather than find the money elsewhere in his agency’s budget, he would simply spend it anyway, at the expense of taxpayers.

And in 2022, the department commissioned a report that was widely ridiculed, which claimed Vancouver’s social safety net cost $5 billion a year. The report was used to claim that public money and resources are being drained in the Downtown Eastside even as the area faces growing poverty.

But that $5-billion figure included $2 billion in federal government funding, such as pension and old age security payouts and employment insurance benefits. And Glacier Media columnist Rob Shaw pointed out that the charities listed among the safety net included hospital foundations, an aquatic fitness program and the Urban Horse Project Society.

Police claim the role of social services

Ward called this version of decriminalization “another one of those facade policies” by the BC government to give the appearance of change without actually creating change.

“[It] gave the police the power to continue to dictate the framing, to continue to say, ‘Well, we’re basically the arbiters of that,’ which is what they did,” Ward added.

“Always, always, always, it’s the police framing.”

That framing includes positioning police as social services providers. The social safety net report included in its $5-billion estimation for Vancouver’s social safety net $317 million in spending from the VPD in 2019, which incidentally is $16 million more than the entire department spent that year.

Police commonly note they are taking on more roles, including as mental health or social workers, which police themselves say contributes to burnout. But while community advocates argue against this mission creep, as mental health calls too commonly end with police killing the subject of the call, police will still push back.

And the decriminalization pilot maintained a role for police as connecting drug users with services, printing off thousands of cards for officers to hand out to people they see using drugs.

Criminalization as identity

Ward said true decriminalization goes beyond thresholds for how much of a drug a person can carry.

“This whole thing didn’t actually have any of the structural changes that we’re talking about here, because it’s not just about: can you carry these drugs around?” Ward said.

“We’re talking about becoming part of society again, as an idea. It’s a movement back into the world.”

Reducing decriminalization to thresholds that one can carry around without being arrested is “ridiculous and shallow,” Ward said, noting that criminalization isn’t just an incident but a process of identifying an outgroup for broader ostracization, in which a person “become[s] a subject of policing.”

“It’s not even necessarily about a charge being laid. … You couldn’t actually exclude someone more thoroughly from society than by saying that you’re outside of the law,” she said.

“Yes, we put them into a cell. … But there’s a process of identification: you’re a criminal.”

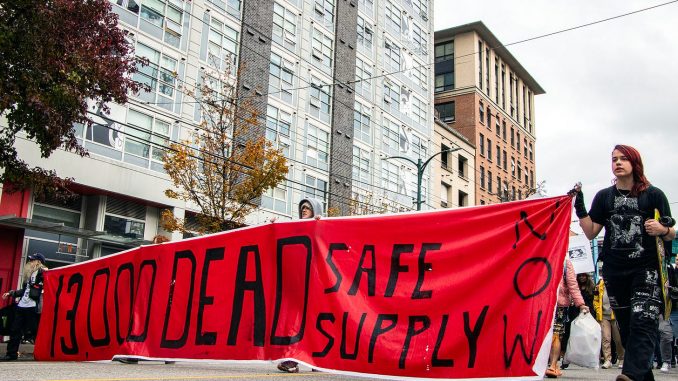

Allies rally for the Drug User Liberation Front in early 2024 following a raid on their compassion club.

Shaping the discourse

That labelling and devaluing of drug users was reflected in the public conversation around drugs during the decriminalization pilot project, Ward said, with many in the public all too ready to believe stories of chaos caused by drug users.

When anonymous sources told journalists drug users were terrorizing hospitals, they reported it uncritically and one-sided in a way they wouldn’t if, for instance, someone suggested police engage in systemic racism.

And discourse abounded of chaos in the streets and alleged increased public drug use that ostensibly was caused by decriminalization, a claim police contributed to, rarely including the context of a 32% increase in homelessness in Metro Vancouver in recent years.

When one video emerged of a couple of people using drugs in a Maple Ridge Tim Hortons, becoming the subject of an entire media cycle, public safety minister Mike Farnworth at the time cited it as a reason to restrict public drug use.

That’s despite the fact that decriminalization didn’t give anyone permission to use drugs in Tim Hortons.

And it’s despite these behaviours being anecdotal and not intrinsic to drug use. But the identity created through criminalization, Ward said, gives permission to paint all of the estimated 225,000 people who use drugs in BC with the same broad strokes.

“Oh, these two guys were smoking in a Tim Hortons, so we’re going to criminalize 225,000 people?” Ward said. “As if that’s representative.”

When corporations taint water supplies, or mislead the public about climate change for decades, or defraud investors, or skimp on quality control, resulting in serious public safety concerns, we don’t see the same widespread agreement that we should criminalize all corporations or CEOs.

Criminalization beyond policing

It doesn’t stop with police, however — to be labelled “criminal” is to be excluded from housing, from employment, from healthcare, from services.

“That kind of goes into the idea of stigma, but it’s much more profound than that. Stigma seems like a meaningless word to me right now,” Ward said.

“You’re not going to find an apartment, so you give up trying. You’re not going to find a job, so you give up trying. So what are you going to do for cash? I guess I’ll go deal drugs. … You stop existing in the legit world. And that’s a really fucked up thing, too, because that’s a failure of everybody.”

Criminalization, then, spans agencies and governments, from police to social workers to housing providers and beyond.

The toxic drug crisis comes at a time in which the decades of defunding most other public institutions — public housing, social services, disability assistance — have been converging into a broader crisis.

Ward said people using drugs in public have become a scapegoat for those failings, despite the behaviour being a symptom of systemic failings and not a cause — and the only response the government can think of is police.

“Our government’s totally just showing its cowardice, and it’s manifest in its response to this,” Ward said.

“This lack of courage is fatal. And it’s really messed up. And the way that the cops have used it to expand their power and their budgets and their authority is really not OK.”

Quick note: I’ve been very slow to publish here, and I owe an explanation to those who have paid subscriptions for this newsletter. I’ve been working on a larger project that is looking like it will be four or five parts, and that has been taking up a lot of the time I have for The Bind. I am aiming to have that finished this month, so look for that coming in the next few weeks.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.