From Filter Magazine, by Sydney Sauer

Compared to the media spotlight on urban homelessness and drug use, rural areas have received far less attention. While this media coverage is often stigmatizing and problematic, the imbalance reflects how rural populations are largely overlooked, and their unique needs neglected.

A study recently published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence seeks to address this gap. The researchers surveyed 3,000 people living in rural areas of the United States who use unregulated opioids or inject other drugs.

A startling 53 percent had experienced homelessness in the past six months, they found.

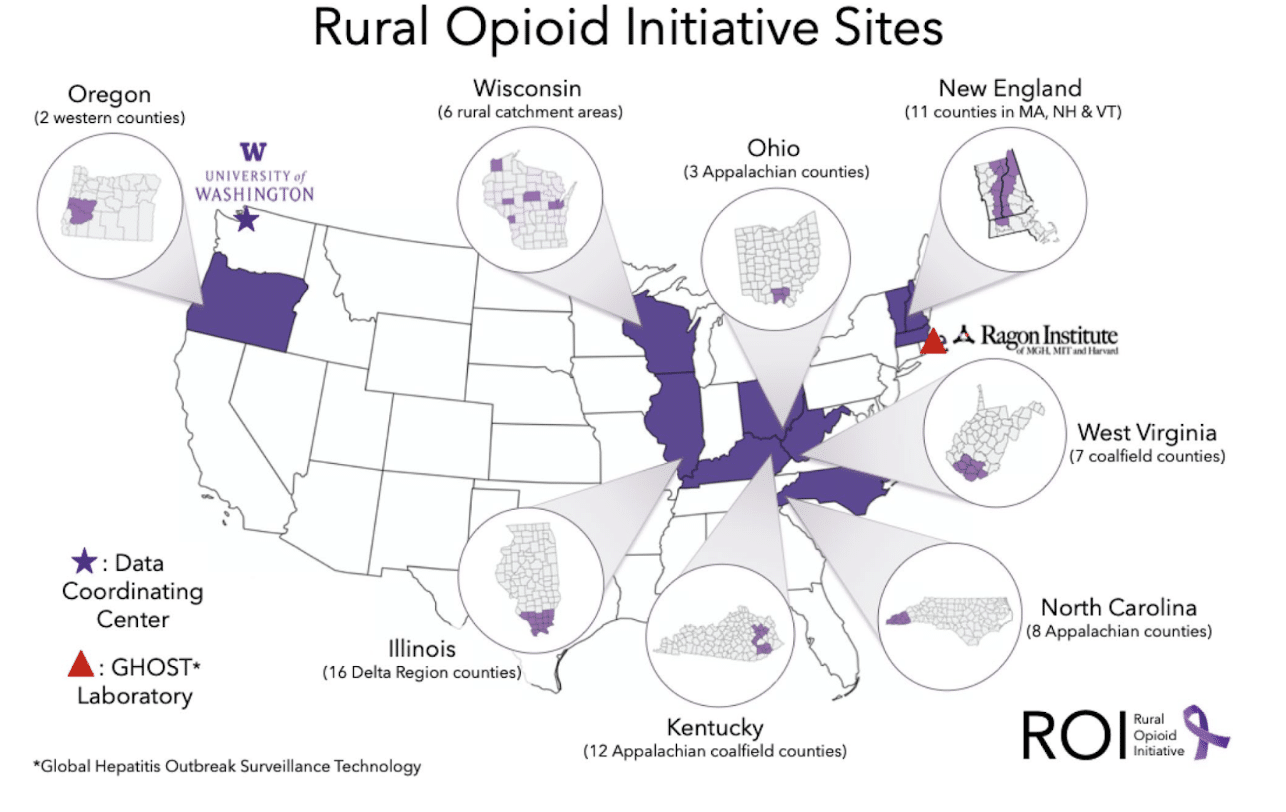

The research stems from a larger project, the Rural Opioid Initiative (ROI), which collects detailed data from eight sites across 10 states to inform overdose prevention efforts.

“Across the different sites, in different states, there was an extremely high number of people that reported experiencing houselessness,” lead author April M. Ballard, an assistant professor at Georgia State University’s School of Public Health, told Filter. “That felt really important for us to highlight.”

Map of study sites via Jenkins et. al. (2022), used with permission of the Rural Opioid Initiative

The ROI survey asks participants a broad range of questions about drug use and health, but for this study, the researchers focused on one main question: “Have you been homeless in the past six months?”

Experiences included living on the streets, living in a car, couchsurfing and other unstable housing arrangements.

Among people who had, their experiences included living on the streets, living in a car, couchsurfing and other unstable housing arrangements.

While 53 percent of respondents around the country had recently been without stable housing, the proportion varied substantially by state. It was highest in Oregon (68 percent) and lowest in Kentucky (36 percent).

Compared to housed participants, unhoused people—the researchers used the term “houseless” to emphasize that people without permanent housing “do not necessarily lack a personal community”—faced significantly greater drug-use risks.

These included higher rates of both bloodborne disease transmissions and overdose. They were also more likely to face barriers to health care access—including lack of transportation, negative prior experiences and unaffordability.

These high-level results are similar to prior research findings in urban settings. However, the researchers noted a few key differences in the rural context.

Encouragingly, they found no difference between housed and unhoused people in rates of hepatitis C/HIV testing and recent substance use disorder treatment. In urban areas, unhoused people are less likely to receive these services. The authors suggested this could be evidence that “targeted efforts in rural areas, including the availability of routine testing at brick-and-mortar and mobile [syringe service programs]” are working.

“In rural areas, people are more hidden.”

On the flip side, Dr. Ballard said that the physical and social infrastructure of rural communities can present unique challenges for unhoused people who use drugs.

“If you’re in a city and you’re walking around or driving around, you’re gonna see people, you know, on the streets,” she explained. “In rural areas, people are more hidden.”

This “invisibility” makes it harder for community members to notice and take care of one another, she continued. And when people do get help, the tight-knit nature of rural communities may represent a barrier to stigma-free support.

“Anonymity is not as easy when you’re living in a small town,” Ballard said. “It’s much easier to get labeled as someone who uses drugs or someone who’s experiencing houselessness.”

Throughout the study, the authors avoided any causal claims about the relationship between substance use and homelessness—perhaps mindful of how their findings might be weaponized to support the misguided media trope that drug use causes homelessness.

Asked how to think about the relationship between the intersecting crises of housing and drug-related harms, Ballard emphasized what she called their “primary upstream drivers”—criminalization and poverty.

“There is criminalization of both houselessness and substance use in the US,” she said. “When you then get involved into the criminal justice system, that then further puts you into cycles of poverty.”

In other words, the strong association between certain types of drug use and homelessness is likely driven by societal factors that cause both outcomes.

“Urban houselessness is talked about a lot … Rural houselessness is not talked about in the same way.”

Ultimately, Ballard hopes that the study will raise awareness of the housing crisis in rural communities and its implications for harm reduction efforts. Fully integrating housing with other harm reduction services is crucial in both urban and rural communities.

“In the US, urban houselessness is talked about a lot, there’s a lot of resources that are put into that,” Ballard said, “but rural houselessness is not talked about in the same way.”

Its erasure is not just a matter of public awareness, but of government awareness. Although the ROI only talked to a tiny fraction of people living at each site, the researchers’ counts of unhoused people far exceeded standard government estimates for the same areas—estimates which are used to allocate funding for interventions.

In Kentucky, for example, the researchers surveyed less than 1 percent of the area’s residents, but found “four to five times as many people experiencing houselessness than was estimated to exist in the entire adult population of the area.” With lifesaving resources on the line, these “drastic underestimates” are likely to have severe consequences.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.